Safe System, Vision Zero, and Sustainable Safety: a scoping review

Abstract

In this study, we provide a scoping review of the research literature on Vision Zero, Safe System and Sustainable Safety. Using a simplified PRISMA approach, we identify 129 studies, describing what year and where the studies are from, which topics the studies are about, and how the terms are used. Using a thematic analysis of the abstracts of the 129 studies, we identify seven main study topics in the studies. The most prevalent study topics are: 1) Case study/Implementation study, 2) Study on principles, 3) Study on practical/strategic use, 4) Study on “readiness”, or factors that inhibit or promote implementation, 5) Vulnerable road users, inequality and social justice, 6) Results of measures and potential, and 7) Future challenges and solutions. We describe knowledge status, knowledge gaps and questions for future research within each study topic. The studies find that entities that have formally implemented the Safe System have relatively low levels of implementation, due to implementation barriers and operationalization challenges. The studies find that it is not necessarily clearly defined what Vision Zero/Safe System is in practice, and that the concept must be interpreted and translated by those who will implement it. Thus, current road safety policies do not fully realise the potential improvements that Safe System can provide, because the principles are not followed to a sufficient extent. A Norwegian study estimate that the number of road fatalities in Norway can be reduced by 50%–70% by following the Safe System principles fully and systematically. Thus, a major challenge, also in mature Safe System contexts, is to facilitate actual Safe System implementation, by mapping barriers/facilitators and Safe System readiness, and defining actions to realise the full potential of Safe System implementation.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Since Vision Zero was adopted by the Swedish parliament as a national road safety policy in 1997 (and Norway in 2001), it has spread to a number of different countries, and it has also become part of the dominant policy discourse in the field of road safety. Inspiration has also come from Sustainable Safety, which was adopted in the Netherlands in 1992. When one of the architects of the Swedish Vision Zero, Claes Tingvall, moved to Australia in 1998, Vision Zero spread to Australia, and the term Safe System was adopted, allegedly as some found the Vision Zero concept provoking (Tingvall, 2022). In the 2000s, this thinking spread to several countries. A number of international organizations began to describe and recommend the Safe Systems approach, including the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), the World Bank, the World Health Organization and the United Nations (UN). These organizations have published a number of reports that explain what the Safe System approach means in practice, within each of the six pillars into which the approach is divided (e.g. ITF, 2022). The United Nations also made Safe System a central element of “The first global decade of Action for road safety 2011–2020”. Safe System is also a key element of the “Stockholm Declaration” from the Third Global Ministerial Conference on Road Safety in 2020 and “The second global decade of action for road safety 2021-2030” (STA, 2019). Moreover, in the Fourth Global Ministerial Conference on Road Safety in Marrakech in 2025, Safe System was the guiding framework for discussions and commitments (WHO, 2025). The Marrakech Declaration, endorsed by ministers from over 100 countries, reinforced the commitment to the Safe System approach (WHO, 2025). The World Bank’s formulation in 2020 represents a point of view that is taken for granted in the road safety world globally:

“The globally accepted best-practice approach to addressing the road safety crisis is the Safe System approach. This consists of a system of ‘pillars’ working together to eliminate death and serious injury.” (World Bank, 2020, abstract).

This illustrates that Safe System has become the state-of-the-art approach for road safety management, and it is recommended to countries worldwide (ITF, 2022; WHO & United Nations Regional Commissions, 2021). The novelty of the Safe System approach is the ethical standpoint that road fatalities cannot be accepted, i.e. there is no ‘optimisation problem’ to solve and we must improve road safety until no one is killed or severely injured. Hence Vision Zero, which is another name for Safe System adopted in Norway and Sweden (referring to the systematic management approach to fulfil Vision Zero). Internationally, the term Vision Zero is used today to describe the goal to be achieved with road safety policies, while Safe System describes the methods to be used to achieve the goal (ITF, 2022).

In practical terms, Safe System has its grounds in four fundamental principles (Green et al., 2022; ITF, 2016):

-

It is human to make mistakes; the traffic system must be designed to tolerate (unintended) errors made by the road users.

-

The traffic system must be designed so that the external forces in accidents do not exceed the human bodies’ tolerance for biomechanical impacts.

-

The responsibility for road safety must be shared by those who design, build, manage, and use roads and vehicles, as well as the providers of the post-crash care and emergency response.

-

All system components must be strengthened to multiply the protection effect; if one component fails, road users should still be protected.

The Safe System approach involves a cultural change (“paradigm shift”) in the sense that the “blame the victim” culture is superseded by “blaming the traffic system”, which throws the spotlight on authorities’ accountability (Green et al., 2022). Additionally, Safe System shifts attention from the prevention of all road accidents to the prevention of the most severe ones with people injured and killed.

The Safe System approach is generally summed up in six pillars, describing how road safety work should be organized (ITF, 2022; WHO & United Nations Regional Commissions, 2021):

-

Road safety management: Multi-sectoral partnerships and lead agencies to develop and lead national road safety strategies, plans and targets; research-based monitoring of implementation and effectiveness.

-

Safe infrastructure: Inherently safe and protective road networks, especially for the most vulnerable (e.g. pedestrians, bicyclists and motorcyclists) road users.

-

Safe vehicles: Standards, consumer information and incentives to accelerate the uptake of active and passive vehicle safety technologies.

-

Safe speed: Speeds within the boundaries of biomechanical tolerance.

-

Safe road users: Enforcement and supplementary measures (e.g. public awareness/education) targeting high-risk behaviors.

-

Post-crash response: Appropriate emergency response, treatment, and rehabilitation for crash victims.

The Safe System approach emerged in the 1990s in Sweden and the Netherlands as a response to a slow-down in traffic fatalities and injuries reduction and a realisation that ‘doing more of the same’ will not bring about the ultimate solution to the road safety problem (Green et al., 2022). Today, the Safe System approach has developed into both a movement for social change globally and a research paradigm, with its own concepts, questions and actors. In this way, the Safe System approach has developed into something more than what Vision Zero in Norway and Sweden and Sustainable Safety in the Netherlands originally was over 25 years ago. Given the spread of these lines of thought over several continents, it can probably also be argued that there are several “Safe Systems” approaches (for example in the USA, in Australia and in Europe).

There is a seemingly high number of studies today, focusing on Safe System and/or Vision Zero as a study topic, or using it or as a way of framing the research. The studies include a wide variety of topics, ranging from road safety policies (Elvik, 2023), to the ethical dimensions of road safety, from the standpoint of vulnerable road users (Davis & Obree, 2020) or to advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) (Jiménez, 2018). The position of the Safe System concept as the dominant paradigm for road safety research and policy, indicates that it would be interesting to see how the term is used and in what contexts. It seems relevant to study e.g.: what is the status of Safe System research today? What are the topics of Safe System research? Can these topics be organized as distinct lines of research? It also seems relevant to describe the knowledge status, knowledge gaps and questions for future research within the different Safe System lines of research. Moreover, given that a large number of the studies are studies of Safe System implementation, it is also relevant to examine the following questions: To what extent are Safe System policies implemented, and where? What are typical challenges related to implementation? Are the Safe System policies sufficiently clear for implementation? What is the potential of (full) Safe System implementation, when it comes to avoidance of road fatalities and serious injuries?

1.1. Aims

The aims of the study are to map the research literature on Vision Zero, Safe System and Sustainable Safety, to:

-

describe key characteristics of the studies, e.g.

a. what year and where the studies are from

b. which topics these studies focus on

c. how the terms are used (i.e. Vision Zero, Safe System, Sustainable safety).

-

provide a qualitative overview of the main study topics in the identified studies

-

describe the knowledge status, knowledge gaps and questions for future research within each of the identified study topics.

2. Method

2.1. Scoping review

We have conducted a scoping review approach, which applies a systematic literature review to fulfil the study aims. We label our approach a scoping review, as our main purpose with the review is to provide an overview of the current knowledge landscape within a given field and identify important knowledge gaps (Dwyer et al., 2023; Levac et al., 2010; Westphaln et al., 2021). Our presentation of the knowledge landscape is done through a theme-based content analysis of the identified studies (section 2.1.4). No reviews of study quality or methods are conducted. We describe the searches and analyses using the main elements of PRISMA: “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses” (Page et al., 2021).

The main purpose of scoping reviews is to map existing literature on a broad topic, identify key concepts, types of evidence, and gaps in research. Unlike systematic reviews, scoping reviews do not usually assess the quality of the studies but aim to provide an overview of the current knowledge landscape within a given field and identify important knowledge gaps (Dwyer et al., 2023; Levac et al., 2010; Westphaln et al., 2021). Scoping reviews comprise six steps. The first step is to define the scope of the review, i.e. which types of research that are to be included in the review and which types or research that are to be excluded. In this study, we search for peer-reviewed studies in scientific journals and also book chapters. The second step is to determine the aims of the review. These are the same as the study aims. The third step is to choose a search strategy. This will involve choosing the scientific databases to search in, and which search strings to use (i.e. combination of search words). This is described in section 2.1.1. The fourth step is article screening, which is described in section 2.1.2 and 2.1.3. The fifth step is data extraction, which is described in section 2.1.4. The sixth step is synthesis of the literature, which involves identifying and summing up the observed main tendencies in the reviewed studies, based on the extracted data.

2.1.1. Search strategy and keywords

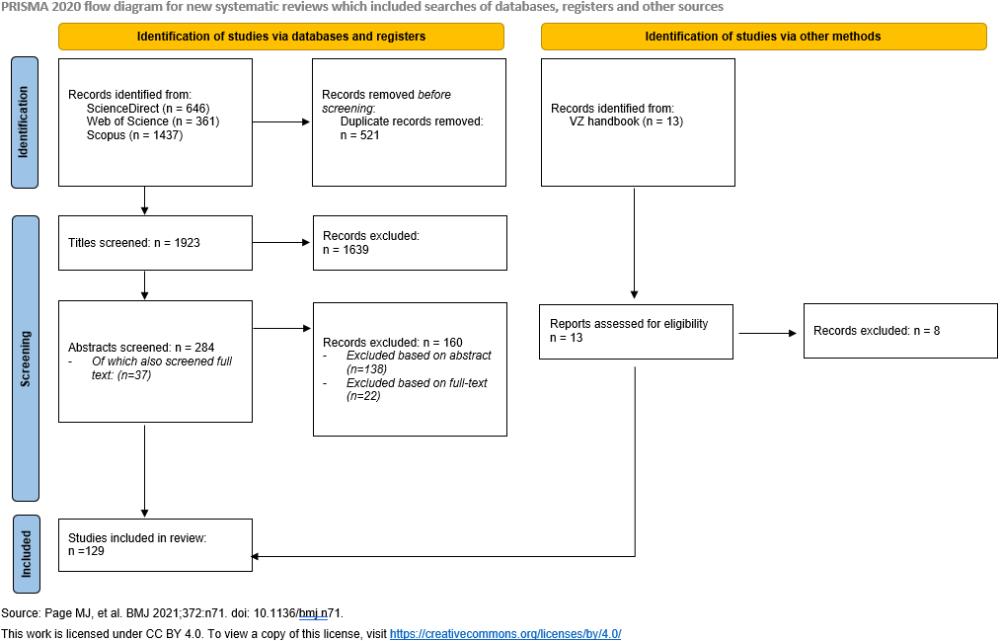

In the literature search, we have used words related to both Vision Zero, Safe System, and Sustainable Safety (cf. Table 1). We searched three scientific databases: Science Direct, Web of Science and Scopus. The searches were conducted in October and December 2024. The main search terms are presented in Table 1. We searched for combinations of these words in keywords, titles and abstracts of the scientific articles. The implementation of this search, and the number of hits it returned is presented in Figure 1.

| Theme | Keywords |

|---|---|

| Vision Zero and safe system | “Vision zero” OR “safe system” OR “safe systems” OR “sustainable safety” |

2.1.2. Criteria for including or excluding studies

We used three criteria when considering which publications to include in the search:

-

scientific publication (scientific journal paper, review paper or book chapter)

-

study about Safe System or Vision Zero or Sustainable safety within road transport (i.e. these are main themes in the studies)

-

English language publication.

2.1.3. Selection of relevant studies

Studies meeting the three criteria were identified through a two-step selection process.

In the first step, we reviewed the titles of all hits from the literature search (n=1923 after removing duplicates) to filter out the clearly irrelevant studies (Figure 1).

We then conducted a title screening, focusing on:

-

correct sector

-

study on Vision Zero, Safe System or Sustainable Safety.

A target study was a study that deals with Vision Zero, Safe System or Sustainable Safety, indicating that this is the main topic of the study.

In the first step, titles that clearly showed that the study did not meet these criteria were screened out. In cases where it was unclear whether the study was about Safe System, Sustainable Safety or Vision Zero for Road Traffic, the study was not removed at this stage. This resulted in = 284 studies for which we screened abstracts.

In the second step, we reviewed the abstracts of the remaining studies (n = 284) to assess relevance. The purpose of this review was first to identify studies that deal with Safe System and/or Vision Zero in road traffic, or Sustainable Safety. We first reviewed abstracts/summaries, and in those cases where it was difficult to assess the relevance of the studies based on this, we also examined the texts in their entirety. The second purpose of this review was to identify the topic on which the study focuses (see section 2.1.5). Two independent researchers were involved in this process, to enhance the reliability of the coding.

Finally, we also added studies that we had identified in other ways than through the literature search and the aforementioned search terms. These were studies that we were familiar with from other projects, or that we found by examining the reference lists of the identified studies. This applies, for example, to five publications from the Vision Zero Handbook (Björnberg et al., 2022), which were not identified though the Scopus search. These were: Lie et al (2022), Corben et al (2022), Belin (2022), Fildes et al (2022) and Stigson et al (2022). After this, we ended up with a total of 129 studies.

2.1.4. Theme-based content analysis of the studies

We conducted thematic analyses of the abstracts of the 129 studies that were identified. A thematic analysis is a systematic method for identifying main themes in textual material (Braun & Clarke, 2006). This involves identifying themes that recur in descriptions of specific topics.

In the first step of the process, the abstracts or summaries were read carefully, and then coded. Two researchers did this to ensure inter-rater reliability. The codes were then systematized and arranged into rough categories. In the next step, the categories were reviewed. In this part of the process, we assessed the categories against each other and against the material, and necessary adjustments were made. Some categories described the same overall concept and were merged, and others stood out as subcategories under a more general theme. The result is overall descriptions that deal with the most prominent themes in the titles and abstracts. In total, we identified seven main themes:

-

Case studies of (some level of) implementation of Vision Zero, Safe System or Sustainable Safety in a country, city, municipality, region or entity at some level.

-

Studies that deal with principles related to Vision Zero, Safe System or Sustainable Safety.

-

Studies about the practical application of Vision Zero, Safe System or Sustainable Safety on some topic, e.g. design of roads, cities, accident investigations.

-

Studies that describe methods for measuring how ready countries, cities, etc. are to implement Safe System, “Safe System Readiness”, and/or conditions that inhibit/promote implementation.

-

Studies that deal with unprotected road users (cyclists, pedestrians, etc.) and/or various ethical issues (inequality, social justice) related to Vision Zero, Safe System or Sustainable Safety.

-

Studies that deal with challenges and themes related to Vision Zero, Safe System or Sustainable Safety in the future.

-

Studies that examine, or report a decrease in fatalities and serious injuries, or the potential for a decrease in fatalities and serious injuries, related to the implementation of Vision Zero, Safe System or Sustainable Safety (or measures based on these approaches).

Several of the studies deal with more than one theme, and we have registered up to two themes per study in the analysis. Based on the coding of the 129 studies, we prepared a data file in SPSS, where the following variables were registered for each study:

-

Author

-

Publication year

-

Countries that the study focuses on, possibly several countries or whether the study is universal, i.e. describes something that applies across several countries.

-

Terms used (1=Safe System, 2= Vision Zero, 3) Both 1 and 2, 4) Sustainable Safety, 5) All three words, i.e. 1, 2 and 4).

-

Primary theme of the study (items 1-7 above)

-

Secondary theme for the study (items 1-7 above)

3. Results

The first aim of the study is to describe key characteristics of the studies, e.g. what year and where the studies are from, which topics these studies are about, and how the terms are used (i.e. Vision Zero, Safe System, Sustainable safety).

3.1. When and where are the studies from?

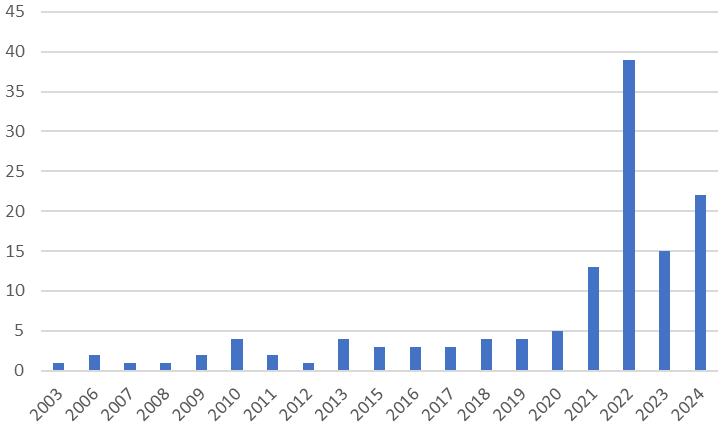

We identified 129 relevant studies on Vision Zero, Safe System and Sustainable Safety through the literature search. In Figure 2 we show which year the different studies on Zero Vision, Safe System and Sustainable Safety are from. Note that the figure does not have a bar for each year, only for the years for which there is at least one article registered.

Figure 2 shows that the number of relevant studies dealing with Vision Zero, Safe System and Sustainable Safety increased from 2021, and that there was a very high number of studies in 2022. This is due to the Vision Zero Handbook (et al., 2022). If this is excluded, we find 12 studies for 2022, i.e. approximately the same number as in 2021 and 2023.

Table 2 shows which countries the various studies are from. Here we give percentages based on the country or countries that the studies focus on (e.g. studies of implementation of Safe System in the US, in Sweden, analysis of VRU accidents in specific countries etc.). Some studies focus on several countries, and the total number of countries is therefore higher than the total number of studies.

| Country | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| US | 27 | 18% |

| Universal | 27 | 18% |

| Sweden | 22 | 15% |

| Single country | 21 | 14% |

| Australia | 17 | 12% |

| Netherlands | 12 | 8% |

| Norway | 7 | 5% |

| Canada | 4 | 3% |

| UK | 4 | 3% |

| LMIC | 3 | 2% |

| Poland | 3 | 2% |

| Total | 147 | 100% |

A total of 14% of the studies involve individual countries mentioned in one or two studies: Denmark, Belarus, China, Ethiopia, Russia, Greece, Italy, Japan, Lithuania, Morocco, New Zealand, Argentina, EU, Germany, India, Iran. These are primarily studies of national implementation of Vision Zero, Safe System or Sustainable Safety, or studies that compare national road safety policies with Safe System principles, to indicate the level of Safe System implementation. The studies that are not focused on any individual country (Universal) discuss e.g. principles or issues without involving country specific data or contexts.

3.2. What concepts do the studies use?

In Table 3 we show which terms the various studies use in their summaries and titles.

| Terms used | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Safe System | 35 | 27% |

| Vision Zero | 66 | 51% |

| Safe System, Vision Zero | 16 | 12% |

| Sustainable Safety | 8 | 6% |

| Safe System, Vision Zero and Sustainable Safety | 4 | 3% |

| Total | 129 | 100% |

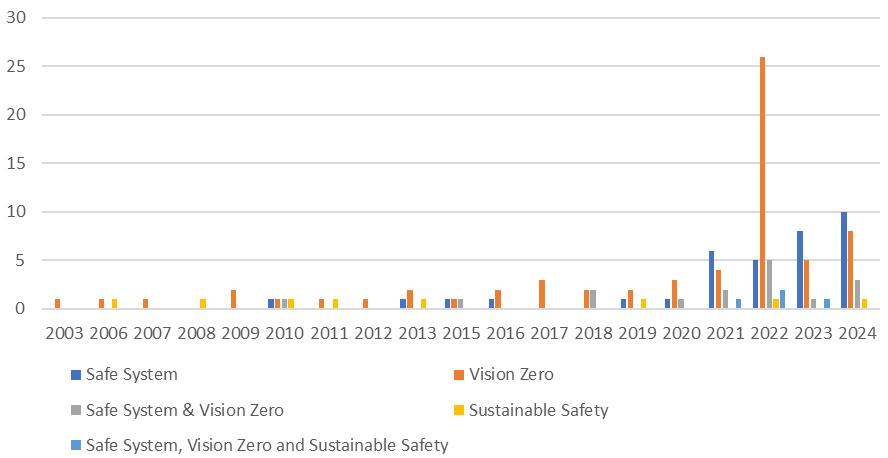

A total of 51% of the studies use the word Vision Zero in the abstract and title (without Safe System), while 27% use only Safe System in the abstract and title. Focusing on which word is used in the abstract and title is interesting, because it says something about the “wrapping”, or framing that the studies use.[1] Figure 3 shows an overview of the year the 129 different studies are from, distributed according to the terms used.

The most striking result in the figure is the high number of studies focusing on Vision Zero in 2022. This is due to the Vision Zero Handbook from 2022. Since Vision Zero is a concept that came before Safe System, and before Safe System became a leading global traffic safety paradigm, one would assume that the Vision Zero concept dominated at the beginning of the period we are looking at, while Safe System studies gradually increase. The figure indicates this to some extent, as the number of Safe System studies increases and is high each year from 2020. Thus, from 2020, it seems that Safe System became an established research concept. Nevertheless, we still see that there also is a high number of Vision Zero studies from 2020, indicating that Vision Zero still is a strong independent research concept.

3.3. How the terms are used

As mentioned, Vision Zero is used as a term for the goal, while Safe System is used as a term for the method to achieve the goal. Given this backdrop, it is interesting to examine why some people use the label Vision Zero and not Safe System in contexts outside Norway and Sweden today. This applies, for example, in the USA, where cities and municipalities, for example, use Vision Zero as a label (and not Safe System). This could be related to the existence of The Vision Zero Network in the USA, which is an NGO that aims to help municipalities, cities and communities to implement Vision Zero.[2] We may speculate whether Vision Zero is a relatively prevalent concept at the local level in the USA, while Safe System is more prevalent at the state/federal level. In any case, there is a strong Vision Zero movement focusing on cities and municipalities in the USA.

We have looked more closely at the 27 studies that we have selected from “The Vision Zero Handbook” to study the use of the term in these studies as an example. Despite the Vision Zero framing of the Handbook, which is related to the Swedish point of departure of the Handbook, 20 of these 27 selected studies write both about Vision Zero and Safe System in the texts. This shows that the separation of studies into Vision Zero studies and Safe System studies to some extent is artificial. The concepts are often used interchangeably, although Vision Zero refers to the goal, while Safe System refers to the method to fulfil the goal. Moreover, it also shows that the words the studies use in the title and abstract is not necessarily meaningful, since the articles also use other terms in the main text itself. However, the title and abstract say something about the intended framing. In any case, our results indicate that choice of study concept and framing is dependent on geography, with Safe System in Australia, Vision Zero at the local level in the US, and Vision Zero in Sweden and Norway.

3.4. Quantitative overview of study themes

In the qualitative thematic content analysis, we have identified seven themes that we ascribe to the studies (cf. section 2.1.4). We attribute at least one primary theme to each study, and often also a secondary theme. It can be difficult to distinguish between what is a primary theme and what is a secondary theme (“what comes first”). In Table 4, we therefore display the percentage of studies covering each theme based on the total number of primary and secondary themes. For instance, 31% of studies have case studies/implementation studies as a primary or secondary theme.

| Primary theme | Secondary theme | Total number | Total percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case study/Implementation study | 49 | 21 | 70 | 31% |

| Study on principles | 20 | 20 | 40 | 18% |

| Study on practical/strategic use | 29 | 8 | 37 | 17% |

| Study on " readiness "; factors that inhibit or promote | 8 | 13 | 21 | 9% |

| Unprotected road users, inequality and social justice | 3 | 14 | 17 | 8% |

| Future challenges and solutions | 11 | 9 | 20 | 9% |

| Results of measures and potential | 9 | 9 | 18 | 8% |

| Total | 129 | 94 | 223 | 100% |

We see that the 129 studies in total cover the seven themes 223 times. There are fewer secondary than there are primary themes. In the Appendix, all the studies are listed in a table according to their primary theme, while the secondary theme is listed in a separate column.

Table 4 shows that three themes dominate the literature. The first theme is the (level of) implementation of Vision Zero, Safe System or Sustainable Safety in a country, city, municipality, region or entity at some level, which accounts for 31% of the themes in the studies. The second theme is principles related to Vision Zero, Safe System or Sustainable Safety, which accounts for 18% of the themes in the studies. The third theme is the practical application of Vision Zero, Safe System or Sustainable Safety on some topic, for example, unprotected road users, which accounts for 17% of the themes in the studies. These three themes are the most prevalent, and they comprise 66% of the 129 studies. Additionally, we have studies focusing on methods for measuring how ready countries, cities etc. are to implement Safe System, “Safe System Readiness”, or studies of factors that promote or inhibit implementation of Safe System. These account for 9% of the themes in the studies. Then we have studies which focus on challenges and themes related to Vision Zero, Safe System or Sustainable Safety in the future, which also account for 9% of the themes in the studies.

3.5. Qualitative overview of the study themes

3.5.1. Implementation studies

A total of 70 studies were identified as case studies of the (level of) implementation of Vision Zero, Safe System or Sustainable Safety in a country, city, municipality, region or entity at some level. We divide the studies into three subcategories (cf. Appendix): 1) Implementation in municipalities or cities, 2) Implementation at a state level or international level, and 3) Implementation in a LMIC context. The implementation studies generally emphasize that none of the implementations are complete, and that challenges remain in integrating these concepts into public policy, ensuring practitioner engagement, and promoting community and cross-sector collaboration. The studies of implementation in municipalities or cities are by and large from the US, describing implementation of Vision Zero initiatives (e.g. Abebe et al., 2024; Evenson et al., 2023; Larsen & Bomberg, 2022; Naumann et al., 2019). In this context, Vision Zero is used as a label and not Safe System. Several of the implementation studies focusing on the national level focus on the Australian context, more specifically the state Victoria (e.g. Cockfield et al., 2022; Corben, 2010; Green et al., 2022, 2023, 2024a). Other studies focus on different countries around the world, especially Sweden (Belin, 2012; Tingvall, 2022), Norway (Elvebakk & Steiro, 2009; Elvik, 2022) and the Netherlands (Wegman et al., 2022), but also Poland (Jamroz et al., 2022; Pistelok & Straub, 2021), Germany (Hell et al., 2022), Canada (Fuselli, 2022) Lithuania (Žuraulis & Pumputis, 2022). Some of these studies typically compare national road safety policies with Vision Zero and Safe System.

Both the studies focusing on the local (city municipality) and the state level highlight that entities that have formally adopted the Safe System have relatively low levels of implementation, due to implementation barriers, and the fact that it is not necessarily clear how the Safe System should be operationalised. Green et al. (2023) highlight the fact that although the Safe System approach has seen significant growth in its application, there has been limited attention to the extent to which the approach is actually integrated into public policy. Their study, which focuses on Victoria, shows that the Safe System is only partially integrated into regional traffic policy, with limited influence on policy frameworks, subsystems, targets and instruments, despite the Safe System being the public policy in Victoria, Australia. Evenson et al. (2023) analyze Vision Zero initiatives in the USA and found that 10.9% of municipalities with a population over 50,000 had introduced such initiatives. Of these, 67.4% had a vision statement, and 59.3% had set a target date for achieving zero fatalities. However, only 4.7% had implemented a performance management system to regularly monitor progress.

The studies emphasize that it is not necessarily clearly defined what Vision Zero/Safe System is in practice, and that the concept must be interpreted and translated by those who will implement it. Elvebakk and Steiro’s (2009) study from Norway emphasize that it is not a given that a vision such as Vision Zero will have the same type of impact outside the country and context in which it was first developed (i.e. Sweden). They find that the vision’s “interpretative flexibility” and the relative lack of public debate during the implementation of Vision Zero in Norway created a situation where key actors focus on different aspects of the vision and at different levels, from theoretical ethical questions to specific practical questions of implementation. Overall, it appears that the relationship between the different levels of the vision is weak. In this situation, actors are relatively free to construct their own interpretations of Vision Zero and what it means in practice, instead of building one common vision. Although the modified Norwegian approach may prove effective, this still raises the question of what a Vision Zero approach actually entails, they write. We find several examples of this in the implementation studies that we review. In a study from Australia Green et al. (2024b) emphasize that the Safe System approach is described in many different ways. They find that practitioners perceive the Safe System as a multidimensional approach with different perceptions of what the overall goal is. The Safe System was seen as both visionary and practical. At the same time, several barriers to implementation were identified, and it was found that these barriers were influenced by the practitioners’ demographic characteristics, roles and organizations. Based on this, it could perhaps be argued that there are as many versions of Vision Zero or Safe Systems as there are countries or places that implement these, because such visions and systems always have to be adapted to the reality in which they are implemented. Some studies also indicate that there may be many “different versions” of Safe System and Vision Zero within countries, as different stakeholders may interpret it differently, because of the concepts’ interpretative flexibility (cf. Elvebakk & Steiro, 2009).

There are several studies from Australia (Victoria e.g. Green et al., 2022, 2023; 2024), where Claes Tingvall (2022) spread Vision Zero to academics and practitioners, after moving from Sweden to Australia. Green et al. (2022) write that the Safe System has been the dominant approach to road safety in Victoria (Australia) for over fifteen years and has guided the development and implementation of policy. However, there has been limited attention to the development and application of the Safe System in a public policy context. In practice, those working with road safety need to clarify the purpose of the Safe System concept to ensure that it is successfully integrated into public policy. Although the Safe System needs to be interpreted and translated, it has sparked increased interest and debate in road safety. In this way, it has helped to advance public policy. Green et al. (2023) emphasise that although the Safe System has influenced road safety policy in Victoria, its integration into public policy is still only partial. Better design of policy instruments and a clearer definition of the role of the Safe System are needed to achieve greater impact. Green et al. (2024a) also note that there is little information on the awareness and support for the Safe System among those who will implement it. There is also too little research focusing on how practitioners understand Safe System. A survey of 469 road safety practitioners in Victoria, Australia, showed that a quarter of the participants were not familiar with the Safe System concept (Green et al., 2024a). The Australia based researchers, Corben et al. (2022) also emphasize that the principles of the Safe System must be adapted and translated into practical guidelines. They underline that practitioners have faced challenges in putting the philosophy and principles into practice. Corben et al. therefore believe that it is important to look at actual practical Safe System solutions, so others can learn what it means in practice.

Six implementation studies focus on Low and middle-income countries (LMIC). These studies highlight the challenges and opportunities in implementing road safety policies in LMIC, with a focus on systemic changes and evidence-based approaches. Abebe (2022) examines road safety policy in Addis Ababa through a Vision Zero perspective, comparing it with Sweden’s well-established approach. The study reveals fundamental differences in how road safety problems are defined and how responsibilities are allocated. In Addis Ababa, road safety is largely seen as an individual responsibility, with limited responsibility attributed to system components such as vehicles, road design and traffic management. This stands in stark contrast to the systems focus of Vision Zero. Neill et al. (2024) evaluate the impact of technical assistance (TA) to translate global road safety research into local implementation, focusing on Accra (Ghana), Bogotá (Colombia) and Mumbai (India). One challenge in transferring knowledge to LMICs, based on Western road safety research, is that the principles may not necessarily be translatable, or implementable without adaptation. Using the Bloomberg Philanthropies Initiative for Global Road Safety (BIGRS) as a case study, the study finds that TA programs can strengthen local road safety capacities and promote the use of research-based interventions. Usami et al (2021) focuses practical Safe System applications from the Safer Africa project.

3.5.2. Studies of principles

We have identified a total of 40 studies that focus on principles related to Vision Zero, Safe System or Sustainable Safety. These studies focus on responsibility, systems thinking, or general road safety management principles. We divide these studies into studies focusing on: 1) responsibility, 2) Systems approach and 3) general discussions of principles in road safety management (cf. Appendix 1).

One of the main themes in the studies on principles is responsibility for preventing traffic accidents. The studies emphasize that Safe System changes the focus from individual responsibility to system responsibility and/or shared responsibility. The studies disagree somewhat on how individual responsibility versus system responsibility is actually weighted in practice, i.e. what shared responsibility entails. In Sweden, the emphasis is on road users following the rules, but system owners have full responsibility and ultimate responsibility, even if road users break the law (Tingvall, 2022). In Norway, the emphasis is on shared responsibility, but the system owners do not have the “ultimate responsibility,” as in Sweden (Elvebakk & Steiro, 2009). Fahlquist (2006) argues that the Safe System policy introduces an explicit distribution of responsibility for traffic safety, where system designers are assigned the ultimate responsibility. By distinguishing between two general types of responsibility assignments—backward responsibility and forward responsibility—the proposed new distribution of responsibility can be better understood. Vision Zero still assigns backward responsibility to individuals, but also explicitly extends forward responsibility to system designers. In a similar vein, Hansson (2022a) discerns between task responsibility and blame responsibility. While traditional traffic safety approaches often focus on blame responsibility (Who caused the crash? Who should be punished?), Vision Zero downplays blame responsibility as the central issue, directing attention to the system conditions that allowed the fatal or serious accident to occur, and how the system can be redesigned to prevent accidents in the future. Hysing (2021) uses the concept of “responsibiliation” as a theoretical lens to analyze changes in road safety governance in Sweden.

Job et al. (2022) highlight two weaknesses in Safe System implementation strategies that hinder effective implementation: (1) interpretations of the principle of shared responsibility and (2) a perception that Safe System only requires the use of several pillars of measures. The authors argue that the common understanding of shared responsibility, which includes the obligation of road users to follow the rules, in practice absolves system owners and operators from their responsibility for road safety. McAndrews (2013) examines road safety as a shared responsibility and a public problem in Swedish road safety policy, pointing out that a major limitation to increasing the status of road safety as a public problem is that road safety is perceived as a private problem.

Another major theme in the studies on principles is the focus on systems thinking. These studies often assess the degree of systems theory in Safe System and Vision Zero and conclude that there is not enough systems thinking in these approaches.

Larsson et al. (2010) point out that while systems theory assumptions are used in other complex and high-risk systems such as nuclear power and aviation, these principles are rarely present in road safety approaches that focus on road users. However, Vision Zero represents a step towards systems theory by building on two axioms: The system must be adapted to human psychological and physical limitations, and the responsibility for road safety must be shared between road users and system designers. Nevertheless, Larsson et al. (2010) believe that there is room to incorporate more aspects of systems theory into Vision Zero.

Mooren and Shuey (2024) argue that effective implementation of the Safe System approach requires integrated systems thinking involving all road safety disciplines. This holistic approach must take into account the interactions between different factors in order to achieve a sustainable reduction in road accidents and injuries. Naumann et al. (2020) highlight that systems tools can identify latent risks in the transport system, analyse factors that lead to high speed and energy exchange, and support the prioritisation of safety through goal setting. They provide a common language for different disciplines and sectors to express their understanding of the interactions between factors that affect road safety problems, and to discuss solutions in line with the Safe System.

Hughes et al. (2015) compare modern road safety strategies in Sweden, the UK, the Netherlands and Australia against scientific systems theory and safety models. Although the strategies have significant similarities, the results show that they have a limited theoretical basis and lack essential aspects of systems theory.

The final theme under principles concerns more general discussions of road safety management principles. Hansson (2022b) provides a typology and overview of principles in safety management, including an analysis of how these principles relate to Vision Zero. He analyses three main categories of safety principles, which are referred to as simple guidelines intended to guide safety work. The first category is aspiration principles, which tell us what level of safety or risk reduction we should aim at or aspire to (e.g. Vision Zero, continuous improvement, cost-benefit analysis, cost-effectiveness analysis). The second is error tolerance principles, which are based on the insight that accidents and mistakes will happen, however much we try to avoid them; leading us to establish measures to minimize the negative effects of failures and unexpected disturbances. The third is evidence evaluation principles, which provide guidance on how to evaluate uncertain evidence.

3.5.3. Studies of practical/strategic use

We find 38 studies that can be defined under the theme of practical application of Vision Zero, Safe System or Sustainable Safety. These studies generally present some practical application of some topic. We divide the studies of practical application into three categories (cf. Appendix 1): 1) Studies with concrete practical advice or examples related to infrastructure, or vehicles, 2) Studies with concrete practical advice and applications of road safety management, and 3) Studies of measures that can help actors who want to implement Vision Zero and Safe System.

3.5.3.1. Studies with concrete practical advice or examples related to infrastructure, or vehicles

Cornelissen et al. (2015) point out that although the Safe System approach has long been recognized as the foundation of modern road safety strategies, system-based applications are still rare. They argue that methods from ergonomics, such as Cognitive Work Analysis (CWA) can play a key role in the design and evaluation of transport systems. By evaluating two intersection designs – a traditional Melbourne intersection and a design based on Safe System principles – the results showed that although the design was different, the system constraints were similar. Cushing et al. (2016) discuss how infrastructure improvements can improve bicycle safety in the United States compared to Sweden. De Bartolomeo et al. (2023) present a risk-based approach to developing an integrated safety management system (SMS) for Italian road infrastructure.

Ghomi and Hussein (2023) study the effects of various pedestrian-oriented interventions in Toronto using a dynamic model. Johansson (2009) proposes solutions based on Vision Zero principles, including fault tolerance and new standards for road and street design. Kubota and Kojima (2024) describe Niigata City’s Vision Zero project at Hiyoriyama Elementary School in Japan, which aims to eliminate serious crashes among children. Lopoo et al. (2024) evaluate a Vision Zero initiative in San Francisco, which reduced the number of serious crashes involving pedestrians and cyclists.

3.5.3.2. Studies with concrete practical advice and applications of road safety management (e.g. goal-setting, indicators, speed management)

Elvik (2023) examines what a road safety policy that is fully consistent with the Safe System principles would mean for road safety. He uses the ITF framework to define criteria for best practice but concludes that these criteria often lack precision and operationalizability. He therefore presents alternative criteria. El Khalai et al. (2024) present a similar approach in a study from Morocco, where they develop a five-step framework for monitoring road safety strategies. Fleisher et al. (2016) introduce “Traffic Safety Best Practices Matrix”, which is designed to help US cities identify effective strategies to advance Vision Zero. They write that there is too little guidance on what Vision Zero entails and what actions can be taken to achieve it.

McHeim et al. (2021) describe how Australian road projects use the Safe System Assessment Framework to include road safety indicators in tender evaluations. Dinh- Zarr et al. (2024) introduce “The Five ‘I’ Framework” for crash investigations, which shifts the focus from causation to prevention. This approach is inspired by other sectors such as aviation and “occupational safety”, highlighting collective actions and system changes for more effective road safety measures.

3.5.3.3. Studies with concrete measures that can help actors to implement Vision Zero and the Safe System

Malik et al. (2020) develop a conceptual framework, called the 4C Framework (clarity, capability, changing context, and community engagement), to evaluate how national road safety policy principles (such as Vision Zero) are actually integrated into local policies. The results show that only a little over a quarter (27%) achieved satisfactory results in capturing overall policy goals.

Naumann et al. (2023) study the “Vision Zero Leadership Team Institute”, which was developed to support communities in strategic planning and goal setting in a collaborative and systems-aware manner. The institute can serve as a model for other initiatives seeking to advance the planning and implementation of Vision Zero.

Schell and Ward (2022) emphasize that while the Safe System approach has been successful in other countries and has great potential in the United States, it requires a significant paradigm shift. For many organizations, its implementation involves a fundamental change in how they:

-

perceive the transportation system

-

interpret their role in the system

-

collaborate with other actors

-

define good results in the system.

Schell and Ward (2022) present a perspective on a process that can increase the likelihood of good results.

In the paper Developing Australia’s highway safety professionals: What can the United States learn?, Shaw et al (2016) highlight how Australia has embedded Safe System principles into training and education of road safety professionals. This contrasts with the U.S., where training tends to be shorter, program-based, and less systematically tied to the Safe System framework. Shaw et al (2016) argue that for the U.S. to improve highway safety outcomes, it should learn from Australia’s Safe System–oriented education, use scientifically validated methods, and build leadership capacity around the Safe System philosophy. This paper describes the Safe System approach as a framework for building professional capacity in road safety. It indicates how both countries can further develop road safety education of professionals.

3.5.4. Safe System Readiness and factors that inhibit or promote implementation

A total of 21 studies describe: 1) Studies focusing on factors inhibiting or facilitating Safe System implementation, or 2) Studies with concrete frameworks to measure and analyse Safe System maturity and readiness (cf Appendix). These studies deal with so-called “Safe System Readiness”, or factors that inhibit or promote implementation. This focus is a consequence of all the implementation studies that say that the Safe System and Vision Zero have not been implemented in practice, or only to a small extent in the countries or places where it has been introduced. These studies point to various factors that inhibit implementation, for example at the political level, administrative level, cultural level, technological level, infrastructure, etc. The studies further highlight the cultural, institutional and societal changes required for successful Safe System implementation. There are relatively few studies which have received this category as their primary label, but several of the implementation studies include information of inhibiting and facilitating factors (i.e. secondary theme), and some of these are mentioned below.

3.5.4.1. Factors that inhibit and promote implementation of Safe System

Several studies emphasize that the principles of the Safe System approach are at odds with cultural norms related to responsibility for accidents and prevention in the countries where the Safe System is being implemented. Johnston (2010) argues that critical elements of the Safe System model conflict with cultural norms of behavior in many Western countries, which hinders the implementation of the most effective safety programs within key institutions and political systems.

Several studies highlight factors that inhibit and promote the implementation of Safe System policies. Otto et al. (2022) write that developing a road safety culture and adopting the Safe System approach requires organizational change. Lasting change is more likely to occur and be sustained when organizations are ready for change. Changeability and willingness are driven by perceptions that:

-

the change is in line with the organization’s culture

-

the organization (e.g. management, employees) is committed to the change

-

the organization has the resources needed to implement the change.

Muir et al. (2018) present a case study of the institutional change required to support the transition to a holistic approach to road safety planning and management in Victoria, Australia. The results show that implementing a Safe System approach requires strong institutional leadership and close collaboration between all key stakeholders involved. Muir et al (2018) found that the challenges in implementing the Safe System strategy were generally neither technical nor scientific – they were primarily social and political. Although many governments claim to be developing strategies based on Safe System thinking, actions depend largely on what politicians consider to be publicly acceptable. However, Muir et al. (2018) write that institutional cultural changes have begun to take root in Victoria.

Also focusing on Safe System implementation in Victoria, Alavi et al. (2023) write that the limited integration of the Safe System approach into road transport management has reduced its ability to significantly reduce serious road accidents. Workshop exercises identified both strong personal alignment with the Safe System principles and systemic practical barriers, as well as suggestions for what could enable better decision-making in line with the Safe System. A roadmap for improvements was developed to address barriers to implementation and implement identified measures.

3.5.4.2. Studies with concrete frameworks to measure and analyse Safe System maturity and readiness

Fosdick et al. (2024) write that although guidance for implementing Safe System exists, local adoption and use of Safe System thinking varies based on organizational structure, history, and traditional spheres of influence in road safety. This research aimed to assess the potential of a model to examine how culturally mature organizations are in relation to Safe System thinking and practice. Understanding how far road safety authorities have come in implementing Safe System principles and practices is important to ensure consistency in implementation and monitoring, as well as to identify where further support is needed. In their study, they develop and test the Safe System Cultural Maturity Model (SSCMM).

Keefe et al. (2024) write that although the importance of cross-sectoral collaboration and the need for a supportive community culture to realize social change is well established, such tools and frameworks have not been used as frequently for road safety initiatives as in other fields. The researchers adapted and used the Community Readiness Assessment (CRA) tool, a well-known model in public health, to assess and inform community-based interventions in seven Vision Zero communities in a US state. Three of the communities were assessed to be at an overall readiness level corresponding to level four out of nine, classified as a “preparation stage”, while four communities received a score of three, or “unclear awareness”. Levels of “readiness” varied across the six dimensions measured, with community-related dimensions (e.g., community culture) receiving lower scores than the “readiness” levels for knowledge, leadership, and resources. Communities with more advanced implementation stages had higher “readiness” scores on average. The results of the assessments provided useful information for further action, especially with regard to discrepancies between the level of readiness of the wider community and the level of readiness associated with management and available resources.

Finally, Stipdonk et al (2024) provides a general overview of three different frameworks to understand Safe System maturity and readiness, including that of Fosdick et al (2024), and those of the Asian Development Bank and ITF.

3.5.5. Unprotected road users, inequality and social justice

A total of 19 of the studies deal with vulnerable road users and/or various ethical issues related to Vision Zero, Safe System or Sustainable Safety, for example with a focus on inequality, social justice, ethics and public health. Although few studies have been labelled with this as the primary theme, it is a relatively prevalent secondary theme. The studies emphasize the need for system changes to achieve a reduction in traffic-related injuries and deaths. The starting point may e.g. be that Vision Zero is car-based. Studies may use an ethical perspective focusing on social justice as a critique of Vision Zero. It is argued that road safety is a universal right, and that one must move away from a way of thinking that accepts a high number of road fatalities. Overall, the studies emphasise the critical need to integrate considerations of justice and prioritise vulnerable road users within the Safe System approach, in order to achieve sustainable improvements in road safety.

Michael et al. (2021) criticize the traditional American approach to road safety, which relies mainly on laws, enforcement, and education campaigns. They argue that this approach is not achieving its goals, as reflected in nearly 40,000 road deaths and 2.7 million injuries annually. In addition, the police stop people in traffic 19 million times annually, and this approach creates persistent conflicts between citizens and authorities and raises concerns about racial and economic injustice, as some groups are stopped by police more often than others.

Davis and Obree (2020) explore, in a British study, the ethical dimensions of road safety, with an emphasis on “freedom from fear” for vulnerable road users. They criticize car-focused policies that prioritize injury reduction over promoting active transportation such as walking and cycling. The authors write that equal rights for vulnerable and protected road users, and freedom from fear of accidents in traffic, have not been central considerations in efforts to reduce the risk for vulnerable road users.

Abebe et al. (2024) study equity and social justice in road safety work using Vision Zero as a case study in New York City. The results show that significant equity and social justice issues arise in the implementation of Vision Zero. These challenges are mainly related to the equitable distribution of road safety measures, the socio-economic consequences of road safety strategies, and the degree of community involvement in the design and implementation of policies.

Piatkowski et al (2021) state that people walking or bicycling are at greater risk of death in rural communities than in cities, and that research is lacking to understand the specific dangers facing VRUs in rural settings, and how to best address these dangers. They underline that Vision Zero is primarily an urban movement and has not generally been pursued in rural communities. Thus, their aim is to develop an understanding of VRU fatalities in rural communities; a “Rural Vision Zero” movement.

3.5.6. Results of measures and potential for avoiding fatalities and serious injuries

A total of 18 studies deal with the reduction in fatalities and serious injuries, or the potential for reduction in fatalities and serious injuries related to the implementation of Zero Vision, Safe System or Sustainable Safety. These studies focus on either: 1) The road safety outcomes of policies, or 2) the potential outcomes of policies (cf. Appendix).

A main conclusion is that current road safety policies in many countries do not fully realise the potential improvements that Safe System can provide, because the principles are not followed to a sufficient extent. Based on analyses from Norway, it is estimated that the number of road fatalities in Norway can be reduced by 50–70% by following the Safe System principles (Elvik, 2023). This is a conservative estimate, which shows that the principles are soundly scientifically based, and that compliance with them can provide considerable improvements in road safety.

Elvik and Nævestad (2023) analyze the impact of Safe System elements in Norway. Statistical models suggest that the implementation of Safe System principles correlates with significant reductions in deaths and serious injuries, likely with greater improvements than traditional approaches. Khan and Das (2024) highlight the effectiveness of the Safe System, focusing on all pillars. Alavi et al. (2023) discuss the limited integration of Safe System principles in Victoria, which has hindered the full potential of the system. Despite partial implementation, the evidence suggests that incorporating these principles into road safety and transport management systems can achieve considerable reductions in serious road accidents. Bergh et al. (2003) report on Sweden’s good results with 2+1 road designs with cable medians. These measures reduced serious accidents by up to 50% and converted potentially fatal accidents into less serious incidents.

Marshall (2018) attributes Australia’s good road safety record - with a fatality rate of 5.3 per 100,000 people (compared to 12.4 in the US) - to Vision Zero principles such as lower speed limits, better road design and stricter enforcement. These measures reduce the overall number of accidents and their severity.

3.5.7. Future challenges and solutions

A total of 20 of the studies deal with future challenges and themes related to Vision Zero, Safe System or Sustainable Safety. These studies deal with challenges, opportunities and innovations within traffic safety. We divide these studies into two categories: 1) Studies focusing on the role of new technology, and automation, 2) Studies focusing on miscellaneous future challenges and solutions and 3) Road safety and sustainability (cf. Appendix).

Automation and new technology. Mofolasayo (2024) examines the significant role of human factors in road accidents and highlights the limitations of driver training and testing in reducing fatalities. The study mentions distraction, fatigue, and substance abuse, and argues that a reasonable degree of automation can reduce these risks. Ehsani et al. (2023) point to the waning effectiveness of traditional road safety strategies and promote the Safe System approach as a promising path to reducing road crashes while ensuring equity. They emphasize the importance of emerging technologies as key tools to promote safety, including AI-powered automated vehicles, impact detection, and telematics.

Miscellaneous. Wegman and Schepers (2024) conclude that the implementation of the Safe System will include opportunities to make cycling significantly safer in the Netherlands. The study calls for improved Safe System measures specifically targeting cyclists, with a focus on road design and systemic risk factors. Williamson (2021) criticizes Safe Systems’ focus on the consequences of accidents rather than the prevention of errors. The study highlights how poor system design - including traffic regulations, infrastructure, vehicle design and assistive technologies - hinders safe behaviour.

3.5.7.1. Road safety and sustainability

Tingvall et al (2022) present the recommendations of the Academic Expert Group (AEG) related to the third global ministerial conference on road safety in Stockholm in 2020. The AEG recommendations, the Stockholm Declaration (and the UN resolution) implies an “expanded understanding of the role of road safety” as part of the concept of sustainability, with a focus on how road safety can contribute to achieving other sustainability goals (e.g. increased active mobility, health). The Stockholm Declaration emphasizes the importance of building synergies between road safety (SDG 3.6) and other sustainability goals. Tingvall et al’s (2022) AEG report provide nine recommendations: Sustainable Practices and Reporting (including road safety interventions across sectors as part of SDG contributions), Safe Vehicles Across the Globe, Procurement: utilizing the buying power of public and private organizations across their value chains, Zero Speeding, Modal Shift, 30 km/h, encouraging active mobility for children and youth by building safer roads and walkways, bringing the benefits of safer vehicles and infrastructure to low- and middle income countries, realizing the value of Safe System design as quickly as possible.

The focus on sustainability and road safety is the backdrop for Wennberg and Dahlholm’s (2024) study of how road safety is implemented at the local level, in line with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Wennberg and Dahlholm (2024) write that the main challenge in a mature Safe System context such as Sweden is how to further develop road safety implementation based on Vision Zero in relation to other sustainability goals from the Stockholm Declaration and UN Resolution 74/299, referred to as an integrated goal approach to sustainability goals. They examine the interaction between road safety and other sustainability goals (synergies), and contradictions between goals and conflicts of interest (challenges), to identify the main factors that enable the implementation of road safety as part of the concept of sustainability. Their empirical study focuses on the situation in Swedish municipalities. Wennberg and Dahlholm (2024) conclude that depending on how road safety goals are operationalized and handled in practice, the result can either be in harmony with, or in opposition to, other goals. They conclude that contradictions between goals or conflicts of interest lie in the solutions. Finally, Van der Knaap et al (2024) also study road safety ans sustainability, using lessons from Safe System evaluation for broader systemic sustainable change. In this study, Safe System is used as exemplar for other sustainability policy areas to learn from.

4. Concluding discussion

4.1. Future challenges and knowledge needs

In the following, we present the main conclusions from the study, when it comes to future challenges and knowledge needs. The conclusions are marked in bold.

4.1.1. We need better implementation of Safe System

We identified 70 studies that constitute case studies of the implementation of Vision Zero, Safe System or Sustainable Safety in a country, city, municipality, region or entity at some level (e.g. Corben, 2022; Elvebakk & Steiro, 2009; Evenson et al., 2023; Green et al., 2022, 2024a, 2024b; Naumann et al., 2019; Shi et al., 2022). The studies generally emphasize that none of the implementations are complete, and that challenges remain in terms of integrating these concepts into public policy, ensuring practitioner engagement and promoting societal and cross-sectoral collaboration. Our study therefore shows that the countries that have implemented the Safe System have not implemented it sufficiently.

Our review shows that increased implementation is important, because it leads to increased road safety, e.g. up to 50-70% reduction in road fatalities in Norway (Elvik, 2023). Eighteen studies in the literature review deal with the reduction in fatalities and serious injuries, or the potential for reduction in fatalities and serious injuries related to the implementation of Zero Vision, Safe System or Sustainable Safety (e.g. Bergh et al., 2003; Elvik & Nævestad, 2023; Khan & Das, 2024; Marshall, 2018; Safarpour et al., 2020). Our review indicates that Safe System has actually not been fully implemented in practice.

In addition, our study shows that relatively few countries globally have implemented the Safe System. A main conclusion is that current road safety policies in many countries do not fully realize the potential improvements that Safe System can provide, because the principles are not followed to a sufficient extent.

4.1.2. We need better clarification of what Safe System implementation actually means

Implementation studies show that it is not necessarily always sufficiently clear how the Safe System should be operationalized (Evenson et al., 2023; Green et al., 2022, 2023). This can obviously be a barrier to implementation. We therefore need better concretizations or operationalizations of what Safe System implementation actually means.

As we have seen in the previous section, studies of the implementation of Vision Zero and the Safe System show that it is not given what such approaches entail in practice, and that these represent general principles that must be translated when they are to be applied by practitioners (Elvebakk & Steiro, 2009; Green et al., 2023, 2024a). In addition, we have seen that those who have implemented the Zero Vision and the Safe System, have often implemented the actual principles and criteria to a small extent (Green et al., 2023, 2024a). In line with this, the literature study shows that there are many different measures that say that they are informed by the Safe System or based on the Safe System and Vision Zero, but these may well be different, because of the translations and adaptations to local conditions. This indicates that there may be as many versions of Safe System as there are implementing countries or communities, or in Elvebakk and Steiro’s (2009) words, we may also assume that there are as many versions of Safe Systems as there are organisations involved in implementation, due to interpretative flexibility.

We find 38 studies that can be defined under the theme of practical application of Vision Zero, Safe System or Sustainable Safety. These studies generally indicate some practical application on some topic or another. Our review indicate that such practical applications of Safe System are much needed for practitioners, as Safe System does not seem to be sufficiently operationalized for them. We divide the studies of practical applications into three categories:

-

Studies with concrete practical advice or examples related to infrastructure, or vehicles,

-

Studies with concrete practical advice and applications of road safety management, and

-

Studies of measures that can help actors who want to implement Vision Zero and Safe System.

The mentioned studies include more or less practical advice on, or examples of how to translate Safe Systems principles into practical policies in given contexts, related to infrastructure, vehicles or road safety management. The final category relates to practical measures to improve Safe System readiness; approaches that can measure and improve awareness, attitudes and knowledge. Finally, it should be noted that the implementation studies indicate that also local adaptation often are required when Safe System solutions are implemented.

4.1.3. We need a better understanding of factors that inhibit and promote implementation

Our review shows that we need a better understanding of factors that inhibit and promote implementation. Tools for assessing Safe System readiness provide a promising approach. A total of 21 of the studies in the literature review focus on factors inhibiting and/or impeding Safe System implementation, or they describe methods for measuring how ready countries, cities, etc. are to implement the Safe System. These latter studies deal with so-called “Safe System Readiness”. This focus on readiness and influencing factors is a consequence of all the implementation studies that say that the Safe System and Vision Zero have been insufficiently implemented in practice in the countries or places where it has been introduced. These studies point to various factors that inhibit implementation, e.g. at the political level, administrative level, cultural level, technological level, infrastructure, etc.

The studies that describe factors that inhibit and promote implementation of Safe System place particular emphasis on traffic safety culture, for example (Johnston, 2010; Otto et al., 2022; Schell & Ward, 2022). Several studies also emphasize administrative and institutional conditions (Alavi et al., 2023; Muir et al., 2018). As an extension of this, several studies have developed tools to measure “Safe system readiness” in different ways. Fosdick, et al. (2024) have developed a Safe System Cultural Maturity Model (SSCMM). Keefe et al. (2024) created the Community Readiness Assessment (CRA) tool. We need a better understanding of factors that inhibit and promote implementation, in order to increase implementation.

4.1.4. We need a better understanding of the system responsibility associated with Safe System

We need a better understanding of the responsibilities and systems associated with Safe System, as this is a crucial component of Safe System. A main theme in the studies on principles related to Vision Zero, Safe System or Sustainable Safety is responsibility for preventing traffic accidents; Safe System changes the focus from individual responsibility to system responsibility and/or shared responsibility. The study results differ regarding how individual responsibility versus system responsibility is actually weighted in practice, i.e. what “shared responsibility” means in practice. In Sweden, the emphasis is on the system owners having full responsibility for creating a road system where road users are not harmed, even if the road user is unable to follow the law (Tingvall, 2022). In Norway, there is not the same emphasis on the system owner having ultimate responsibility, even if road users break the law (Elvebakk & Steiro, 2009). Thus, Norway has an interpretation of shared responsibility which is different from Sweden.

Another main theme in these studies is the focus on system thinking. These studies often assess the degree of systems theory in Safe System and Vision Zero and conclude that there is not enough systems thinking in these approaches (Larsson et al., 2010; Mooren & Shuey, 2024; Naumann et al., 2020). Several of the studies emphasize that Safe System has a strong focus on system owner responsibility, such as in Sweden, but that many countries do not include this, and that this therefore implies a lower degree of Safe System implementation and that the potential for traffic safety gains is not fully realized.

4.2. Suggestions for future studies

4.2.1. Safe System in the future: “Integrated Goal Approach”

Wennberg and Dahlholm (2024) write that the main challenge in a mature Safe System context like Sweden is how to further develop road safety implementation based on Vision Zero in relation to other sustainability goals from the Stockholm Declaration and UN Resolution 74/299, referred to as an integrated approach to the SDGs. Such an integrated approach to the SDGs involves seeing road safety as a natural part of and as a prerequisite for other sustainability goals. This way of understanding road safety, as a prerequisite for other sustainability goals, is the official global strategy we have for achieving the goal in UN Resolution 74/299, to halve the number of road deaths in the world by 2030 (STA, 2019).

ITF (2022) describes the different stages of development in the Safe System, and it can be indicated that the highest maturity level in the Safe System is about full goal achievement related to all the different pillars of the Safe System (cars with the highest score in Euro-NCAP, roads in line with Safe System principles and manuals). Wennberg and Dahlholm (2024) indicate, however, that an “Integrated Goal Approach” can be seen as the highest level of Safe System implementation (at least in a mature context). This level is not only about maximum road safety, but also about increased active mobility, increased public health and increased use of public transport. In road safety thinking, it is often assumed that increased proportions of pedestrians and cyclists are associated with more injuries and deaths in traffic. Wennberg and Dahlholm (2024) emphasize, however, that there does not necessarily have to be a conflict between road safety and increased active mobility, if road safe solutions are seen as a prerequisite for increased active mobility.

In our literature review, we have seen that Vision Zero has been criticized for being “car-based” and that several have called for a stronger focus on vulnerable road users. “The Integrated Goal Approach” to Safe System can address this. Seventeen of the studies we identified deal with vulnerable road users and/or various ethical issues related to Vision Zero, Safe System or Sustainable Safety, e.g. with a focus on inequality, social justice, ethics and public health (e.g. Abebe et al., 2024; Cushing et al., 2016; Davis & Obree, 2020; Hirsch et al., 2021; Michael et al., 2021; Mohan, 2019; Shi et al., 2021). The studies emphasize the need for system changes to achieve a decrease in traffic-related injuries and deaths. Several of the studies further argue for road safety as a universal right, and that one must move away from a mindset that accepts a high number of road fatalities. Collectively, the studies emphasize the critical need to integrate considerations of fairness and prioritize vulnerable road users within the Safe System approach, in order to achieve sustainable improvements in road safety.

4.2.2. We need knowledge about measures that can strengthen the implementation of Safe System

We need a better understanding of factors that inhibit and promote implementation, in order to increase the implementation of the Safe System. Once we have gained such knowledge, we need knowledge of measures that can enhance the implementation of the Safe System, i.e. measures that can be used to weaken factors that prevent implementation (e.g. cultural scepticism towards restrictive measures, insufficient systems thinking), and strengthen measures that promote implementation (road safety commitment among politicians and administrative leaders and in the population). We know what is needed to increase road safety. Relevant measures mentioned by Elvik (2023) are, for example, increased police enforcement, lower speed limits, safer vehicles and safer roads. Introducing these measures probably requires cultural changes (increased acceptance of lower speed limits) and increased commitment among politicians, which leads to more financial resources to road maintenance and the police.

4.2.3. Automation and Safe System

A current topic in several of the studies is the relationship between automated vehicles and the Safe System, and the possibility of further improving traffic safety through automation (Ehsani et al., 2023; Jiménez, 2018; Lie et al., 2022; Mofolasayo, 2024). Increased automation can potentially weaken the importance of human error, which is the basis for our need for a Safe System, and thus create an even safer traffic system. Automation therefore resonates well with the Safe System approach. However, we do not know to what extent this potential can be realized, or whether the interaction between humans and technology creates new risk surfaces, e.g. due to behavioural adaptation or interaction challenges. Lie et al. (2022) write, for example, that automated vehicles must be better than human drivers are, and that their safety systems and system owners must adapt the transport system to both erring humans and erring automated vehicles.

4.2.4. Simplification of the Safe System approach

Our study indicates that the Safe System approach and Vision Zero may seem quite comprehensive and complex for the organisational settings that aim to implement them. These approaches involve underlying principles, pillars, and they require specifications. When we look at the more practical applications, we see that a core in these often are to contain kinetic energy by focusing on: 1) separation of road users with different levels of physical protection and speeds (VRUs and others) through infrastructure measures and 2) reducing and or adapting speed levels. When spreading Safe System to other parts of the world, e.g. LMICs this could be a main focus or starting point. These principles also resonate well with the Sustainable Safety approach, at least as it was in the start. The containment of kinetic energy also relates to universal principles which apply all over the world, and may thus be subject to fewer discussions related to relevance and transferability of policy.

4.2.5. What is the difference between Safe System implementation at local level versus state level?

We may speculate whether Vision Zero is a relatively prevalent concept at the local level in the USA, while Safe System is more prevalent at the state/federal level. As a continuation of this, it would be interesting to see whether the content is different in Safe System versus the local Vision Zero studies, and whether the local Vision Zero approach is translated into something different at the local level than at the national level. This examination can also be conducted for all the mature applications that we have observed across continents in our study, e.g. in Scandinavia, Netherlands, the US and Australia. Does Safe System look the same across these implementation contexts?

4.3. Methodological limitations and strengths