How accurate do car drivers report their travelled speed before an accident: a comparison with insights of the Event Data Recorder

Abstract

Statements of drivers are often used to gain insights into accident causations, whose understanding is an important factor for the development of effective prevention strategies. The coming into effect of the General Safety Regulation 2019 led to an increasing availability of objective vehicle data in the form of Event Data Recorders (EDR) in Germany as well as the whole European Union. This creates the possibility to examine the accuracy of the driver statements in more detail. Among others, maladjusted vehicle speed is an important crash contributing factor. Therefore, a good understanding about the quality and applicability of the drivers' reported speed can be important. The goal of the present study is to examine the accuracy of speed reports from German drivers in the context of accident research. To this end, the reported speeds and speed violations were evaluated with respect to their consistency with the EDR data. Additionally, it was investigated whether there is a relationship between the accuracy of the statements and the role in causing the accident on the one hand and the time elapsed between the accident and the report of the driven speed on the other hand. Based on data from the Audi Accident Research Unit (AARU), this study compares drivers' self-reported speeds prior to an accident obtained by standardized telephone interviews with the respective recorded EDR speeds of the crash vehicles. It was shown that driver reported speed violations significantly less often and to a smaller extent than they were committed based on the EDR data. The reported speeds were significantly lower than the recorded speeds from the EDR data. Furthermore, this effect was significantly stronger for the other accident participants, which tended to underestimate their speed more than the accident causers. This result might be explained by a certain group of other accident participants which were driving very fast (> 200 km/h) on the motorway, as is elaborated in detail in the discussion. There was no significant correlation between the accuracy of the reported speed and the timing of the respective interviews. In conclusion, the drivers’ statements regarding the driven speed were found to be relatively inaccurate, which is why they can only be used with caution and in conjunction with more reliable data. Still, the reported speed can be valuable to evaluate the general plausibility of the drivers' statements concerning the accident.

1. Introduction

Understanding the causes of traffic accidents is essential for the development of appropriate countermeasures (Tivesten, 2014; Weber et al., 2013). Reports from drivers involved in traffic accidents are a central and well-established instrument for analyzing accident causation (McClafferty et al., 2005; Tivesten, 2014; Versteegh, 2004). Although the quality of witness statements has been a major research topic in forensic psychology for a long time, the specific evaluation from the perspective of accident research psychology is comparatively new (Risser & Schützhofer, 2015; Strigl, 1996). For an appropriate use and assessment of driver statements in accident investigations it is, however, necessary to understand how reliable the information is and where possible inaccuracies occur (Risser & Schützhofer, 2015).

An increasing number of modern cars in Germany is equipped with an Event Data Recorder (EDR) that provides detailed information on the driver's behaviour in the last five seconds leading up to an accident. The EDR records various parameters, including the speed, the steering angle, and the activation of the brake and accelerator pedals (Bosch Automotive Service Solutions, 2015). The implementation and dissemination of EDRs and similar devices have proceeded differently across the world (Blanc et al., 2023; Gleave et al., 2014). While the recording of accident data by the EDR has been regulated in the USA through prescribed standards since 2006, its mandatory introduction in the EU is still relatively new (Blanc et al., 2023). In accordance with the General Safety Regulation 2019, an EDR is compulsory in the EU for all newly homologated vehicle types since July 2022 and for all new registrations since 2024 (ADAC, 2020; Regulation (EU) 2019/2144, 2019). However, many automobile manufacturers had already equipped their vehicle models for the European market with EDRs on a voluntary basis before the mandatory introduction or have enabled data access in their models globally (ADAC, 2020; Blanc et al., 2023). The growing number of cars equipped with this system provides objective real-world accident data and offers a new opportunity to examine the quality of driver statements regarding the pre-crash phase in Germany, too.

Excessive and inappropriate speed choice is identified as a relevant contributing factor to crashes, particularly in fatal ones (European Commission, 2021; Fondzenyuy et al., 2024). In in-depth accident analyses the estimation of the speed driven before an accident is usually not (solely) based on driver statements, but rather relies on a physical reconstruction of the accident, taking into account trace evidence and the severity of damage (Johannsen, 2013; Weber et al., 2013). However, there are various methods to examine accident-contributing factors, and such detailed information is not available in all cases (Johannsen, 2013; Tivesten, 2014). In addition, physical accident reconstruction often requires making certain assumptions when objective vehicle data (e.g., from the EDR) are unavailable (Burg & Moser, 2017). In such cases, driver statements might be used as an indication (Burg & Moser, 2017; Versteegh, 2004). Therefore, it is of interest to examine how accurately drivers report their travelled speed before an accident.

Studies across different research fields have revealed relatively weak relationship and substantial differences between objectively measured and self-reported speeds and speed violations (for review see e.g. Bailey & Wundersitz, 2019; Wåhlberg, 2009). Haglund and Åberg (2000) hypothesized based on their findings in a field study on speed choice, that although drivers are generally aware of their chosen speed level, they lack precise knowledge of their speed at specific points during their journey due to irregular checks of the speedometer. For this reason, the authors assumed that drivers guess their speed in retrospect. This assumption is further supported by the notion that speed regulation, like many other aspects of the driving task, is executed automatically (Corbett, 2001). For this reason, drivers are often unable to consciously recall their speed and instead seem to estimate it based on the speed limit (Corbett, 2001; Haglund & Åberg, 2000). Additionally, factors such as the imprecision of the speedometer (Haglund & Åberg, 2000), inattention, and limitations in speed perception (Corbett, 2001) were discussed as contributing to the inaccuracy of subjective speed estimates. Furthermore, research on speed perception has shown that drivers are unable to accurately estimate their driving speed without the aid of a measuring device and tend to underestimate their own speed (e.g. Hussain et al., 2019; Recarte & Nunes, 1996; Schütz et al., 2015). In addition to these explanations, various forms of bias can distort self-reported behaviour, such as social desirability, self-deception or the altering of information through lies or omission (for discussion see e.g. Lajunen & Özkan, 2011, as cited in Bailey & Wundersitz, 2019; Wåhlberg, 2009).

A few studies have examined the consistency between drivers' self-reported speeds before an accident and speeds derived from accident reconstruction, finding low concordance (Staubach & Lüken, 2009) and a relevant underestimation of most drivers (Versteegh, 2004). As mentioned, accident reconstructions may partially rely on assumptions when objective data is unavailable (Burg & Moser, 2017), and discrepancies in speed estimates between engineering approaches based on objective evidence and in-vehicle data recordings have been observed (Chung & Chang, 2015). Since EDR data has been available for over 20 years in some parts of the world, first studies on the accuracy and reliability of driver statements (McClafferty et al., 2005; McClafferty et al., 2003) and other sources, such as police assessments (e.g. daSilva, 2008; Elsegood et al., 2019), were conducted several years ago. McClafferty et al. (2005) compared the drivers-reported speeds with EDR data from the crashed vehicle using cases from the Transport Canada collision investigation programme. The drivers' self-reported speed was obtained either through interviews conducted as part of a pilot study or from police reports and was compared with the maximum speed recorded by the EDR. The majority of drivers reported a lower speed than recorded by the EDR, with an average deviation of 14 km/h. In 60% of the cases the discrepancy exceeded 10 km/h. The extent of misestimation varied, including both much higher and much lower reported speeds. Generally, drivers tended to report a speed close to the speed limit, except when they were turning at the time of the accident. As a result, drivers' speed estimates were most accurate when they were travelling close to the speed limit just before the accident. Based on the EDR data, speed violations were frequently observed, including instances of high (≥ 20 km/h) or even severe (≥ 40 km/h) violations. In contrast, only a few drivers admitted to exceeding the speed limit by 10 km/h or more. However, it is important to note that some drivers reported their speed to the police, which is why the possibility of sanctions may have influenced the reported speed in these cases. The existing findings indicate that the consistency between drivers' reported speeds and EDR-recorded speeds before the accident is relatively low. To the best of our knowledge, this is the only systematic comparison of drivers' self-reported pre-accident speed with EDR data, and no similar study has been conducted in Germany as of yet.

This study aims to evaluate the accuracy of speed reports provided by drivers in Germany in the context of accident research. Both the consistency of drivers' reported speed with the recorded speed values of the EDR and drivers' reporting of speed violations are examined. To identify potential underlying relationships, the present study explores whether the accuracy of the reported speed varies according to the role in causing the accident. However, Versteegh's (2004) study did not reveal significant differences in the accuracy of drivers' speed estimates depending on their culpability. Over time, memories of the accident may be distorted by various factors and forgetting effects may occur (Risser & Schützhofer, 2014; Strigl, 1996; Wåhlberg, 2009). For this reason, the optimal timing for interviewing drivers in the context of accident research is in question (Pund & Nickel, 1994; Staubach & Lüken, 2009). Therefore, the relationship between the time elapsed after the accident and the accuracy of the speed estimates is also considered. Previous studies have produced contradictory results in this regard. While Pund and Nickel (1994) reported a deterioration in speed information over time based on individual case analyses, Staubach and Lüken (2009) found no significant differences in the accuracy of reported speeds within the first three months after the accident in their systematic investigation. The findings of this study may offer a better understanding of the quality and applicability of drivers' reported speed in accident research and help draw conclusions about the usefulness of questioning drivers about their driven speed, given the increasing availability of objective EDR data.

2. Methodology

A non-interventional, retrospective registry-based study was conducted using car accidents analysed by the Audi Accident Research Unit (AARU). The AARU is an interdisciplinary research project by the Regensburg University Medical Centre in Germany in cooperation with the AUDI AG (Weber et al., 2013, 2014). Traffic accidents are investigated in depth from psychological, technical, and medical perspectives to gain comprehensive insights into their causations, sequence of events, and consequences. The AARU analyses traffic accidents in Bavaria involving an Audi Group vehicle that was at most two years old at the time of the accident. In addition, at least one of the following criteria must be met regarding the severity of the accident: one or more persons were injured; at least one airbag deployed; at least one vehicle was severely damaged. An additional prerequisite for the complete analysis is the consent of the individuals involved in the accident. Once this had been obtained, these persons were interviewed and the involved vehicles were examined.

2.1 Sample

All accidents for which the analyses by the AARU had been completed by October 2023 were considered for the study. For a total of 121 drivers from 119 accidents in the AARU database, both an interview with the driver and EDR data from the accident vehicle were available. Accordingly, for two accidents, this data set was available for two of the involved drivers. Six drivers reported having no clear memory of the accident. The reports of 115 drivers from 113 accidents were therefore comparable with respect to their content. About half of these drivers (51.3%) primarily caused the accident. The remaining drivers constituted the group of other accident participants. The classification of accident responsibility was based on the assessment of the psychological accident research team. Drivers identified as being primarily responsible for the accident due to the accident cause analysis were classified as 'accident causers'. Although accidents are typically not caused intentionally, this term is used in the present paper for reasons of clarity and consistency, without implying deliberate action. Nevertheless, drivers in the group of other accident participants may also have causally contributed to the occurrence of the accident through their behaviour. On average, the drivers were 41.3 years old (SD ± 17.8). The accident causers were significantly younger (Mdn = 32.0 years) than the other accident participants according to a Mann-Whitney test (Mdn = 44.0 years, U = 1232.50, z = -2.35, p = .019, r = -0.22). The majority of the drivers (78.3%) were male, while 21.7% were female. The drivers had held their driving licences for between 1 and 62 years, with a median of 19.5 years. The drivers had covered 1 000 to 90 000 kilometres in the last twelve months preceding the accident. The median was 27 000 kilometres. The drivers had been driving the accident vehicle for a duration between one day and three years before the accident, with a median of four months. The accident causers had held their driving licences for a significantly shorter period (Mdn = 14.5 years) than the other accident participants according to a Mann-Whitney test (Mdn = 24.0 years, U = 1088.50, z = -2.53, p = .011, r = -0.24). That same test found no significant differences regarding the distance travelled in the last 12 months before the accident or the duration of vehicle usage. In the following, different parts of the sample were selected according to the specific research question. The drivers included in each analysis are presented at the beginning of each result section.

The analysed accidents involving the 115 drivers took place between the years 2017 and 2023. About one fifth (20.9%) were single-vehicle accidents. In all other accidents, at least one other participant was involved, with a maximum of six. About one quarter (24.3%) of the accidents occurred within urban areas, 46.1% on rural roads, and 29.6% on motorways or roads with similar characteristics. The majority of accidents happened during daylight (73.9%), nearly a forth (24.3%) in darkness, and 1.7% during twilight. Based on the accident scenario categorisation by Feifel and Wagner (2018), the accident types defined by the German Insurance Association (2016) and further accident information, the analysed accidents can be divided into the following groups:

-

Crossing and turning scenarios accounted for 31.3% of the accidents, with 19 drivers failing to yield the right of way and 17 drivers having the right of way in the accident situation.

-

Rear-end collisions made up 30.4% of the accidents. In these cases, eight drivers were hit by a following vehicle and ten drivers hit the rear end of the car in front. Furthermore, 14 drivers hit a vehicle that was changing lanes, one driver changing lanes was rear-ended and two overtaking drivers were involved in other rear-end scenarios.

-

Lane departure scenarios accounted for 33.9% of the accidents, with 15 drivers leaving their lane due to excessive speed, while 13 did so for other reasons. Additionally, there were 11 drivers who encountered another vehicle coming towards them in their lane.

-

The sample also contained 4.4% accidents belonging to other scenarios. In four cases, a child or animal unexpectedly entered the road, and in another case, one driver's vehicle was hit by another vehicle after a previous crash.

2.2 Data Collection

2.2.1 Interview

As part of the psychological accident analysis, standardized telephone interviews are conducted with the drivers to gather their perspective on the accident occurrence (Weber et al., 2013, 2014). The interview consists of open-ended questions exploring the accident development and the final moments preceding the accident, as well as closed-ended questions focusing on the pre-accident conditions, the driver's condition, and their driving experience. As part of this, the drivers are asked in an open-ended format to estimate how fast they were driving before the accident and about the speed limit at the accident site.

The telephone interviews with the drivers of the current study were conducted by the responsible psychological personnel, who were specially trained for this task. The key points of the conversation were documented during the interview and later recorded in a report and persisted in a database. The interview timing varied among participants based on when the accident was reported to the AARU and the duration required to obtain consent for participation in the research project. The interviews were conducted between 2 and 181 days after the accident, with a median of 27 days. Prior to the interview, the drivers were informed that their responses would be treated confidentially, used solely for research purposes, and would not be shared with third parties. They were also made aware that all information was voluntary and the objective was not to determine fault, but to investigate the causes of the accident.

2.2.2 Event Data Recorder (EDR)

The EDR ‘means a device or function in a vehicle that records the vehicle's dynamic, time-series data during the time period just prior to a crash event (e.g., vehicle speed vs. time) or during a crash event … , intended for retrieval after the crash event’ (49 CFR Part 563, 2006, p. 191). CFR 49 Part 563 in the United States and the UN Regulation No. 160 (2021) in the European Union, set legal requirements that regulate (among other aspects) the collection, storage, and availability of EDR data.

Upon a storage-relevant event, the EDR stores certain pre-crash data elements over a period starting five seconds before the event until it is triggered, at a rate of two data points per second (Blanc et al., 2023). These include, but are not limited to, the speed, and the activation of the brake and accelerator pedals (Blanc et al., 2023; Bosch Automotive Service Solutions, 2015). It has to be emphasized, that the EDR data do not allow for determining the moment of an action or system intervention within a higher precision than the 0.5-second sample interval (Chen et al., 2022).

The speed recorded by the EDR is defined as ‘the speed indicated by a manufacturer-designated subsystem designed to indicate the vehicle's ground travel speed during vehicle operation’ (49 CFR Part 563, 2006, p. 194). Depending on the speed signal used, discrepancies between the actual physical speed and the recorded speed may occur, e.g., when the speedometer signal is applied (Blanc et al., 2023; Burg, 2016). This is because, in accordance with legal requirements, the speed indicated by the speedometer is slightly higher than the actual speed due to speedometer pre-calibration. Additionally, the accuracy of the speed values in the EDR can be affected by wheel slip due to heavy acceleration or braking, and by large side slip angles caused by skidding (Blanc et al., 2023). According to Blanc et al., the speed values recorded by the EDR, if based on the speedometer data, are quite accurate and within the tolerance range for speedometer deviations for constant driving speeds as well as moderate acceleration and deceleration.

Upon obtaining the required consents, the vehicle is inspected by the technical team of the AARU (Weber et al., 2013, 2014). As part of this process, the EDR is retrieved if available and if this is technically feasible. Based on all collected data (e.g. EDR data, trace evidence, vehicle damages, and driver statements), the engineers perform a physical reconstruction of the accident. Hereby, the EDR data is evaluated and interpreted in the context of the specific accident. Conclusions are then drawn with regards to whether and how the driver reacted prior to the accident.

2.3 Analysis strategy

2.3.1 Reported speed violations

To examine how often drivers reported speed violations that are visible in the EDR data, the approach of McClafferty et al. (2005) was used. Accordingly, the maximum speed recorded by the EDR was compared with the speed limit at the accident site to determine the frequency and extent of speed violations in the EDR data. The analysis also considered potential changes in the speed limit during the pre-crash phase. Subjective speed violations were evaluated by comparing the reported speed with the stated speed limit. When drivers specified a speed range, the highest value was used for analysis. A speed violation was defined as any speed exceeding the speed limit by at least 5 km/h. Based on the changes in sanctions in the national catalogue of fines (Kraftfahrt-Bundesamt, 2023), four categories were defined: no speed violation (≤ 4 km/h), violations of 5–10 km/h, 11–20 km/h, and more than 20 km/h.

2.3.2 Accuracy of drivers' reported speed

Accurate temporal matching is essential for a valid comparison of subjective and objective speed data, but it also poses several challenges. The main reason for this is that the specific time point in the accident which the driver's reported speed referred to was not always clear, as the interview question, ‘How fast were you driving before the accident?’ allows for some interpretation. This holds especially if the manoeuvre before the accident involves speed changes that are reflected in the EDR data, e.g. turning into a street. As a consequence, the question arose of which value to select from the EDR speed data for an appropriate comparison. Based on previous literature and example cases, standardized rules for determining the comparison speed from the EDR were established to maximize the objectivity. The conceptual basis behind these rules and their formulation are briefly presented in the following paragraph.

Apart from the study by McClafferty et al. (2005), whose choice of comparison speed did not seem suitable for this specific question, there was no study that compared drivers' self-reported speeds with the speed values recorded in the EDR. However, among others, daSilva (2008) systematically compared the driving speed indicated by the police officer in the police report with the speed data from the EDR for General Motors vehicles, using the National Automotive Sampling System (NASS) Crashworthiness Data System (CDS) database (daSilva, 2008; National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2006). For this comparison, he selected the reference speed from the EDR based on the role in the accident and any potential reaction prior to the accident (daSilva, 2008). Although his comparison is not based on drivers' self-reported speeds, the study offers an approach for a reasonable selection of a comparison speed from the EDR. Similarly to the presented study, the aim of daSilva’s study was to select a speed value from the EDR that accurately represents the driving speed before the collision. A selection based on the driver's potential reaction seems reasonable insofar as the comparison speed is chosen at a moment when the driver has either just become aware of the impending accident or—if no reaction is observed—is likely still unaware of it, ensuring that no reactive speed change has occurred. Accordingly, the identification of the reference speed value from the EDR was orientated on the strategy of daSilva. Thus, the selection was also based on a potential driver response in the pre-crash phase but independent of the role in the accident involvement. If the driver showed a reaction before the accident according to the assessment by the technical team of the AARU, the speed value two time steps (corresponding to 1 s in total) before the onset of the first response was chosen from the EDR data. On the other hand, if the driver did not react, the most recent recorded speed value was selected. To take the potential inaccuracies in the EDR data into consideration (see Section 2.2.2), in case of an anti-lock braking system and/or electronic stability control system activation without a preceding or simultaneous driver reaction, the speed was selected one time step before the start of the first system activity. In some instances, the developed selection strategy evidently did not result in the desired temporal alignment of subjective and objective speed information. In these cases, an individual approach was developed through expert discussion.

If the driver reported a speed range, the mean speed value was used for comparison. In some cases, the driver did not specify a numerical speed but described driving at walking speed or cautiously entering the intersection. As there is no standardized definition of ‘walking speed’ in Germany (ADAC, 2024), a speed range of 5 to 10 km/h was assumed in these cases, with an average of 7.5 km/h applied for analysis. The reference speed from the EDR was taken as the best available measure for the actual driving speed. The deviation of the driver's reported speed from the recorded speed was calculated by subtracting the selected EDR value from the subjective speed information. Positive values indicate drivers' overestimation, whereas negative values represent an underestimation. It was considered whether the analysis should be based on absolute speed deviations in km/h or on relative speed deviations, defined as the percentage by which the driver's reported speed deviates from the recorded speed. However, using the relative deviations would have led to very high deviations in the lower speed range as compared to the high speed range, where even large deviations would have resulted in negligible relative deviations. This would have made it harder to compare the various accidents as they occurred in a wide range of speeds. Therefore, the absolute speed deviation was chosen for the further analysis.

2.3.3 Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using the statistics software IBM SPSS Statistics, version 29. As the sample exhibited a relevant number of extreme values with respect to the deviation of the drivers' reported speed from the EDR speed, non-parametric statistical methods were employed. The statistical test procedures used to examine each research question are outlined in the respective results section. For all statistical tests, a significance level of α = 0.05 was applied.

3. Results

3.1 Speed violations

EDR data from 87 vehicles were analysed for potential speed violations. Because Germany, unlike most other countries, has motorway sections without a speed limit, 28 cases that occurred on such sections were excluded from the analysis. A comparison of the maximum speed recorded by the EDR with the speed limit at the accident site revealed that 36.7% of drivers exceeded the speed limit by at least 5 km/h. Among those drivers, the highest recorded speed excess was 113 km/h, while the median speed excess was 15.5 km/h.

A comparison between driver-reported speed violations and those recorded in the EDR data was possible for 75 drivers. Eleven drivers did not report their speed prior to the accident and/or the speed limit at the accident site. One more case with a speed violation detected in the EDR data was excluded because the self-reported speed referred to a point in the driving manoeuvre of the pre-crash phase where a deceleration had already happened. A marginal homogeneity test revealed that the drivers' speed reports differed significantly from the EDR data regarding speed violations (z = 4.59, p < .001). Table 3.11 shows that 14.7% of the drivers stated that they had exceeded the speed limit by 5 km/h or more. In contrast, such speed violations were visible in 36.0% of the EDR data. In cases where no speeding was reported, the EDR data still indicated speed violations in approximately one-quarter (26.6%) of these cases. Drivers predominantly reported smaller speed violations of 5 to 10 km/h whereas larger speed excesses of more than 20 km/h were not reported at all. Drivers with large speed violations had a stronger tendency of admitting to a speed violation than drivers with speed violations up to 20 km/h. However, the amount of the conceded violation was smaller than the recorded one. For recorded speed violations between 5 and 20 km/h, most drivers did not admit to those violations.

| EDR (n) | Reported speed violations (n) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No violation | 5–10 km/h | 11–20 km/h | >20 km/h | total | |

| no violation | 47 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 48 |

| 5–10 km/h | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| 11–20 km/h | 9 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| >20 km/h | 3 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 9 |

| total | 64 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 75 |

A comparison between the reported and the actual speed limit showed that 18 drivers had a misconception about the valid speed limit. There was an equal distribution of too high and too low reported speed limits. Among the drivers committing a speed violation, six drivers that did not acknowledge it or admitted to a smaller violation assumed a wrong applicable speed limit. In five of these cases, there was a change of the applicable speed limit shortly before the accident site and in most of these cases, the report of the correct applicable speed limit would have led to admitting to a (more severe) speed violation.

3.2 Accuracy of drivers' reported speed

The reported speed of 97 drivers was assessed regarding its accuracy compared to the EDR data. The remaining drivers did not report their speed prior to the accident and/or their description of how the accident occurred was not plausible compared to the reconstruction based on the EDR data (Tschech, 2025). Therefore, the selection of an appropriate reference speed from the EDR data was not possible for those drivers.

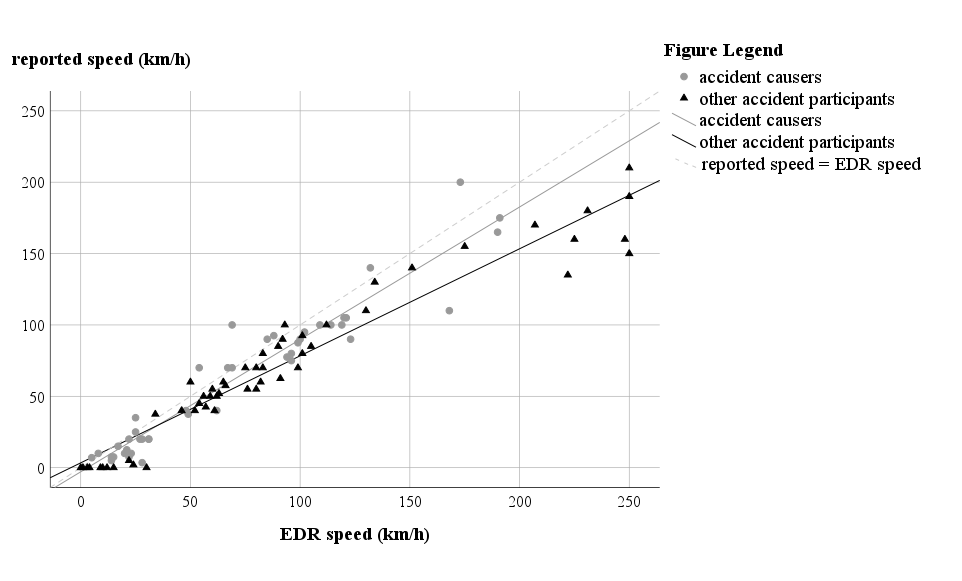

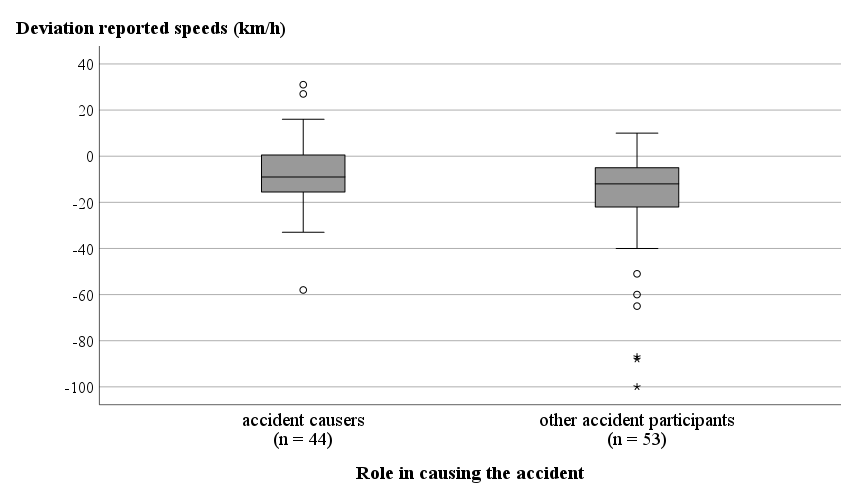

A Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed that the drivers' reported speed was significantly lower than the reference speed from the EDR (z = -6.89, p < .001, r = -0.50). As can be seen in Figure 3.1, 83.5% of the reported speeds are below the dashed light grey diagonal, which marks the perfect match of reported and recorded speed. For more than half of the drivers (53.6%), the reported speed differed by more than ±10 km/h from the EDR speed. In general, the deviation of the reported speed was in a range of 100 km/h below and 31 km/h above the recorded speed (see Table 3.2). For the 81 drivers that reported a speed lower than the recorded speed, 60.5% of the reported speeds deviated by more than 10 km/h. On the other hand, from the 14 drivers that reported a speed higher than the recorded speed, 64.3% deviated by less than 10 km/h.

| n | Mdn | Max (-) | Max (+) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accident causers | 44 | -9.0 km/h | -58.0 km/h | 31.0 km/h |

| Other accident participants | 53 | -12.0 km/h | -100.0 km/h | 10.0 km/h |

| total | 97 | -11.0 km/h | -100.0 km/h | 31.0 km/h |

As is evident from Figure 3.1, the reported speed differs stronger from the EDR speed for speeds above 150 km/h than in the lower speed range, with the biggest differences occurring in a group of drivers that went 200 km/h or faster in the fast lane of the motorway. Furthermore, a group of drivers stood out that stated to be (almost) at a standstill, but was in motion according to the EDR data. These drivers decelerated due to traffic or a driving manoeuvre before being rear-ended by a following vehicle.

Drivers varied with respect to how close their reported driving speed was to the valid speed limit they reported in the interview. The analysis included only drivers who had been involved in accidents on roads with an applicable speed limit. While the 26 drivers that were driving with a constant speed before the accident mostly reported a speed close (±10 km/h) to their reported speed limit, most of the 41 drivers that executed a driving manoeuvre (e.g. turning or braking) reported a larger deviation from their reported speed limit. While the drivers with a constant speed had a tendency to report a driven speed slightly below the speed limit they reported in the interview, the EDR data showed that they were mostly driving faster than they reported. As described in Chapter 3.1, the speed limit reported by the drivers did not always match the speed limit actually applicable at the accident site.

3.2.1 Role in causing the accident

A Mann-Whitney-Test yielded a significant difference between the accident causers and the other accident participants with respect to the deviation of the reported speed and the EDR speed (U = 861.50, z = -2.21, p = .027, r = -0.22). It could be ruled out that the age of the drivers (rs = -0.07, p = .529) and the length of driving licence ownership (rs = -0.05, p = .625) can serve as an explanation for this difference.

Compared to the recorded speed, the other accident participants reported lower speeds more frequently and to a greater extent than the accident causers, as is shown in Figure 3.1 and Figure 3.2. Thus, the regression line for the other accident participants in Figure 3.1 is flatter than that for the accident causers. Remarkable in this context is the group of extremely fast drivers (≥ 200 km/h) in the fast lane of the motorway that had the largest deviations. These drivers were categorised as other accident participants. Although they contributed causally to the occurrence of the accident due to their choice of high speeds, the primary cause was attributed to the lane changers who failed to yield the right of way. This attribution is based on the principle that, on sections of the German motorway without a speed limit, the presence of fast-moving vehicles must generally be anticipated, and right of way must be granted to them accordingly.

3.2.2 Time interval between accident and interview

No significant correlation was found between the deviation of the reported and the EDR speed and the time interval between the interview and the accident (rs = 0.06, p = .588). A subgroup-specific analysis did not reveal any significant associations for accident causers (rs = 0.11, p = .458) or other accident participants (rs = 0.06, p = .640) in this respect.

4. Discussion

Drivers reported speed violations significantly less frequently than they occurred according to EDR data. However, some limitations must be considered before the interpretation of this result. As described in Section 2.2.2, discrepancies between the actual physical speed and the recorded speed in the EDR may occur, depending on the speed signal used. For example, when the speedometer signal is applied the recorded speed is slightly above the actual physical speed due to speedometer pre-calibration (Blanc et al., 2023; Burg, 2016). Therefore, the observed speed violations in the EDR data and their extent are no exact quantities. Additionally, since speed violations were absent in most cases, only a limited number of cases allowed for a comparison between the driver-reported and EDR-recorded speed violations. The tendency of drivers not to admit their speed violations was also observed by McClafferty et al. (2005), even if a part of the drivers' reported speeds were obtained from police reports. As a result of the present study, it can be concluded that drivers tend not to report speed violations in the context of accident research, even if they do not have to expect immediate sanctions by doing so. This might originate from various conscious and unconscious processes as they were discussed with respect to the validity of drivers' statements in the context of accident research and self-reported speed behaviour in general, like social desirability (e.g. Corbett, 2001; Tivesten, 2014; Wåhlberg, 2009) or fear of potential consequences (e.g. Clarke et al., 1998; Gründl, 2005). Not admitting to minor speed violations might be due to drivers not (exactly) remembering their driven speed and often tending to guess it based on the applicable speed limit (Corbett, 2001; Haglund & Åberg, 2000). Many drivers take the pre-calibration of the speedometer into account for their speed choices, which results in a speedometer speed slightly above the speed limit (Picco et al., 2025). Possibly, drivers also consider this pre-calibration for their reported speed, subtracting the assumed margin. Detailed analyses in this study showed that some drivers might not report speed violations due to misconceptions about the applicable speed limit, a phenomenon also observed by Versteegh (2004). Such speed violations might have happened unconsciously, as discussed by Corbett (2001). Drivers committing very large speed violations (> 20 km/h) as evident from the EDR data reported rather smaller speed violations. Since excessive speed was the cause of the accident in most such cases, not admitting to a speed violation at all might have seemed implausible, and these drivers possibly admitted a smaller speed violation as a concession.

There was a significant deviation between the reported and the recorded speeds. Most drivers reported a speed that was lower than the recorded speed from the EDR and the deviation was more than ±10 km/h in the majority of the cases. Due to the potential mentioned imprecisions of the EDR speed, the calculated deviations are no exact quantities. As the temporal assignment of the reported speed was difficult, inconsistencies concerning the temporal alignment of reported speed and reference speed from the EDR cannot be completely ruled out, which might have influenced the amount of the deviations. The observed inaccuracies in the reported speeds are consistent with previous research where similar deviations were found (McClafferty et al., 2005; Versteegh, 2004). The same reasons like discussed above for the non-admitting of speed violations can serve as possible explanations for the observed deviations in the reported speed. As was shown also in the present study, drivers that were driving with a constant speed tended to report a speed close to the speed limit, which coincides with the results of previous research regarding self-reported speed (Corbett, 2001; Haglund & Åberg, 2000; McClafferty et al., 2005).

The accuracy of the drivers' reported speeds differed significantly depending on the role in causing the accident, albeit not in the direction one might assume. Compared to the recorded speed, the other accident participants reported lower speeds more frequently and to a greater extent than the accident causers. While the effect size was rather small, it differs from the results by Versteegh's (2004) study, which did not find significant differences between those quantities. It has to be considered that this analysis only contained the cases where the course of the accident was described plausibly by the driver. The main part of the implausible statements was hereby made by the accident causers, where this classification was partly also due to a strongly varying reported speed (Tschech, 2025). Standing out was a group of extremely fast drivers in the fast lane of the motorway that were other accident participants and rear-ended a lane changer. These showed the largest deviations in the reported speed, with the reported speed far below the recorded speed. It is possible that the small effect concerning the accuracy of the reported speed depending on the role of causing the accident is mainly originating from this group. For these drivers, a possible explanation for reporting a speed that was too low could be the concern about legal, social, or personal consequences due to partial responsibility for the accident. On the other hand, this might also be an effect of the psychophysiological limitations of human speed perception, since these drivers drove with a speed of 200 km/h or above. It is conceivable that drivers estimate their speed even less accurately in the range of such high speeds than for lower speeds. Recarte and Nunes (1996) hypothesized that the improved accuracy in speed estimation at higher velocities (120 km/h) observed in their study could be attributed to a greater amount of auditory and somatosensory information, such as increased engine and road noise. One could assume, once a certain speed is reached, these signals no longer increase significantly, which could make it harder to judge speed differences at very high levels. While this is a reasonable assumption, to the best of our knowledge there is currently no research backing this claim for such high speeds.

No significant correlation was found between the accuracy of the drivers' reported speed and the timing of the interview. This result aligns with the findings of Staubach and Lüken (2009), that the accuracy of the drivers' speed reports does not change substantially during the first three months after the accident. The experiences described by Pund and Nickel (1994), which indicated a worsening in the accuracy of the reported speeds over time, were not observed in the present study. However, the majority of the interviews took place within the first three months after the accident. Therefore, it is possible that the deteriorations in the reported speeds described by Pund and Nickel (1994) become relevant only when the time elapsed after the accident is even longer. The constructive memory processes involved in the retrospective reported speed seem to take effect independent of the time interval between the accident and the interview. The same holds for the other influences on the reporting of speed described above, e.g. social desirability.

The present study has certain methodological limitations. As already mentioned above, the recorded speed from the EDR can suffer from small imprecisions, which propagates to all derived quantities, e.g. speed deviations. Furthermore, the interviews with the drivers were conducted with the main goal of analysing the causes of the accidents, not specifically for a comparison with the EDR data. This led to the described difficulties in aligning the reported speeds with the recorded speeds, also due to the phrasing of the question. Accordingly, one specific reason could be that the interviewer was unable to do the temporal assignment or the documentation of it sufficiently well in some cases. The way questions are asked is discussed as a potential source of distortion in self-reports (for review see Bailey & Wundersitz, 2019). Also, a certain bias caused by the interviewer and the assessor cannot be fully ruled out. Even if some measures were employed to enhance the objectivity of the results in both areas, some form of unconscious cognitive distortion cannot be fully dismissed. For instance, there might be a bias due to the knowledge about the role of the driver in the accident and the accident in general (as discussed by Risser & Schützhofer, 2014). An independent evaluation of the accuracy by a second assessor would have been desirable to determine the objectivity of the assessment. As the presented analysis is only a part of a larger investigation, this was not feasible due to capacity reasons, mainly because of the complexity and the necessary in-depth knowledge on part of the assessor. However, the fixed rules for the selection of the reference values allowed for a quite objective approach which only seemed to fail for individual cases. In these cases, an expert discussion was performed to improve objectivity. The potential reasons for the discrepancies in the reported speeds were only hypothesized based on existing literature. The possibility of interviewing a selected subsample to explore underlying factors was considered. However, due to ethical concerns and methodological constraints, this approach was not pursued.

Concerning the interpretation and generalizability of the results it must be taken into consideration that this study is not based on a random sample and the analysed accidents and drivers are not representative, neither for all car accidents in Germany nor the complete AARU sample. This is due to the general sample selection of the AARU as described in Section 2 and the necessity of an interview with the driver and existing EDR data. Therefore, a selection bias may have affected the results. Two central factors are relevant in this context: Firstly, only drivers with relatively new vehicles from a specific vehicle segment were included in the sample. The choice of vehicle type is associated with various personal characteristics, including demographic factors, and personality traits (e.g. Choo & Mokhtarian, 2004; O’Connor et al., 2022), attitudes, and lifestyle (Choo & Mokhtarian, 2004). Secondly, all drivers voluntarily agreed to participate in the accident research and the associated interview. This may have led to self-selection effects. Between 2017 and 2023, only an average of 40.7% of all individuals involved in the accidents who were contacted by the AARU gave their consent to participate. However, this percentage refers not only to the drivers, but also to passengers and other involved persons. Some of the results are specific for Germany, since there are sections of the motorway without a speed limit in this country, which permits speeds that are not allowed on public roads in almost all other countries. It should be noted that memories and statements of drivers can be consciously and unconsciously influenced by information from third parties, such as accident witnesses (e.g. Loftus, 2019; Loftus et al., 1978). While this is a general source of influence for driver statements in the context of accident research, such processes cannot always be tracked and revealed, thus possibly distorting the results. As the sample contained various accident scenarios and pre-crash phases, some of the observed differences might be due to different accident mechanisms and some potential effects might have gone unnoticed. Hence, a separate examination of the accuracy of the drivers' speed reports in specific accident scenarios in future studies would be valuable, allowing for a comparison between these scenarios.

5. Conclusion

The results of the present study show that the drivers' statements concerning the driven speed prior to the accident are relatively inaccurate. Therefore, these statements have to be used with caution in the context of accident research. They can merely be used as indicators, which have to be cross-checked and validated with other accident data, ideally by a physical reconstruction based on EDR data. Due to the relatively low accuracy, asking the drivers about their driven speed seems less useful for the actual determination of the speed itself, especially if more reliable data, like from an EDR, is available. However, these statements can still be useful in conjunction with the EDR data to evaluate the general plausibility of the drivers' statements concerning the course of the accident and to draw conclusions about the accident causation. In the doctoral thesis on which this study is based, not only speed but also other aspects, such as the course of the accident, were compared and evaluated (Tschech, 2025). During this assessment a very high speed deviation (amongst other factors) justified the implausibility of the reported circumstances of the accident in some cases. The primary criterion for the evaluation of the drivers' statements with respect to their plausibility regarding the course of the accident was the origin of the accident. Statements were classified as plausible or implausible depending on whether they were generally consistent with the reconstructed sequence of events leading to the accident based on the EDR data. However, the current analysis showed that a precise formulation of the question is crucial to avoid misinterpretations. Also, the interviewer should closely coordinate with the driver to determine the moment in the pre-crash phase the statements refer to. Additionally, there are still many vehicles in Germany that have no EDR installed, and in some cases there may be no EDR data after an accident, e.g. if the EDR is destroyed. In those cases, the subjective drivers' statements concerning the driven speed may still be a valuable indicator. As already stated, these statements have to be used with their limitations taken into account and the precautions mentioned above. Therefore, the results of this study provide a useful groundwork for a better understanding of the drivers' reported speeds and their limitations in the context of accident research.

Acknowledgement

The presented research work is part of a PhD thesis by one of the authors (Karen Tschech) at the University of Regensburg. Parts of the reported results were presented at the 66th Conference of Experimental Psychologist in March 2024 and the Symposium on Accident Research and Road Traffic Safety (UFO25) in June 2025.

CRediT contribution

Karen Tschech: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft. Thomas Schenk: Project administration, Writing—review & editing. Daniel Popp: Writing—review & editing. Volker Alt: Funding acquisition, Writing—review & editing. Stefanie Weber: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—review & editing.

Declaration of competing interests

The authors report no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The methods for data collection used by the AARU and subsequently in the present study have been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Regensburg. The initial decision was made in 1998 and the currently valid update was made in 2013 (Reference 98-085).

Funding

The Audi Accident Research Unit (AARU) is a cooperation between the Regensburg University Medical Center and the AUDI AG. Reflecting the interdisciplinary approach of the research project, the Regensburg University Medical Center provides the medical and the psychological expertise, while the AUDI AG contributes the technical expertise. Based on the contract of cooperation the research work of the AARU and this study is fully funded by the AUDI AG.

Declaration of generative AI use in writing

During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT-40 in order to check the grammatical correctness of the written text and to improve the clarity of language. The outputs were reviewed and revised by the authors who take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Editorial information

Handling editor: Stijn Daniels, Transport & Mobility Leuven | KU Leuven, Belgium.

Reviewers: Ralf Risser, Palacký University Olomouc, Czechia; Dick de Waard, University of Groningen, Netherlands; Sam Doecke, The University of Adelaide, Australia.

Submitted: 11 March 2025; Accepted: 9 December 2025; Published: 19 December 2025.