The importance of infrastructure and road safety culture for pedestrian safety: a comparison of three European and three African countries

Abstract

Walking is a primary mode of transport in urban Africa, yet it remains unsafe, challenging, and unpleasant. In contrast, several European countries have implemented systematic policies to promote walking through Safe System principles. This study compares pedestrian safety in three African countries (Tanzania, Ghana, Zambia), with three European countries with excellence in road safety and Safe System implementation (Norway, the Netherlands, Sweden). Data includes focus group interviews with African road users and stakeholders (n = 48), fieldwork, and surveys of pedestrians in the African (n = 753) and the European countries (n = 1109). The aims are to examine: (1) pedestrians’ perceptions of infrastructure, traffic situation, and traffic safety culture, (2) pedestrians’ accident involvement and (3) factors influencing pedestrians’ accident involvement. Our results show that pedestrian safety in the studied African countries is not only related to material factors (e.g. safe system infrastructure); it is also related to cultural factors (e.g. societal status of pedestrians, traffic safety culture). We discuss how policy strategies should address both types of factors. Our results indicate that Safe System implementation in the studied African countries is likely to improve pedestrian safety. However, working with infrastructure is not sufficient; cultural factors, including the sociocultural position of pedestrians, must also be addressed. We also discuss how infrastructure, traffic situation and traffic safety culture are related to larger framework conditions, like urban planning, public transport systems, and economy.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Walking is the most common mode of transport in Africa, either as the main mode itself, or in combination with other transport modes, e.g. public transport (UN Habitat, 2013). Reviewing different studies, Benton et al. (2023) report that walking accounts for between 50% and 90% of daily trips in many African cities. By contrast, walking typically accounts for around 30% of daily trips in European cities, where car use remains the dominant mode, making up approximately 50% of trips in many urban areas (European Commission, 2022). Benton et al (2023) report that the people living in low-income countries walk out of necessity, primarily to reduce, or avoid the high expense of public transport, which would comprise between 30% and 49% of household income (Porter et al., 2020).

Although walking is a primary mode of transport in urban Africa, it remains unsafe, challenging, and unpleasant (Benton et al., 2023). This is mainly because a Safe System walking infrastructure is inadequate, or non-existent in African countries (UN Habitat, 2013). As of the latest data, the road traffic fatality rate in the African region remains the highest globally, with 19.4 deaths per 100,000 population. This rate has increased by 17% since 2010, with nearly 250,000 lives lost on the continent’s roads in 2021 alone (WHO, 2023). Despite accounting for only 15% of the global population and 3% of the world’s vehicles, Africa represents 19% of global road traffic deaths (WHO, 2023).

Pedestrians are particularly affected by traffic accidents in African countries. Vulnerable road users (VRUs), defined as pedestrians, cyclists and users of two- and three-wheelers, are the largest but most underprivileged road user group in Africa, disproportionally impacted by traffic accidents with fatalities share of 50% of all road users killed in traffic (WHO, 2023). Pedestrians have a fatality share of 33% in Africa (WHO, 2023). Benton et al (2023) states that in some countries this proportion is even higher, e.g. 58% in Mozambique. Statistics indicate that an average of 618 people were killed each day in traffic accidents in Africa in 2021, and that 206 of these were pedestrians - a number which is likely to be underestimated due to underreporting of such accidents (WHO, 2023). Benton et al (2023) mention that the World Road Association’s (PIARC) catalogue of design safety measures estimates that investment in pedestrian facilities could reduce crashes by up to 90%. At the same time only 21 out of 54 African countries have developed walking policies and plans, and only two countries in Africa have country-specific pedestrian infrastructure guidelines (Uganda and South Africa) (Benton et al., 2023).

Inadequate or lacking pedestrian infrastructure is a major cause of low pedestrian safety in African countries, in spite of the fact that walking is the major transport mode. In contrast, several European countries have implemented systematic policies to promote walking through Safe System principles, e.g. Sweden, The Netherlands, Norway, France, Germany.

An important road infrastructure challenge in LMICs is the lack of physical separation between vulnerable road users and motorised traffic. This direct exposure to high-speed vehicle traffic in developing countries leads to a considerably larger accident risk for pedestrians compared with pedestrians in Western European countries, which often have separated facilities for vehicles and pedestrians (Tulu et al., 2013). Pedestrians are vulnerable to mortality and morbidity because they are directly exposed to traffic with little to protect them in the event of a collision. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that, globally, 88% of pedestrians traverse unsafe roads, which contributes directly to pedestrian injuries and deaths. Tulu et al (2013) cite an in-depth study in a developing country, which shows that non-existing sidewalks, high volumes of motorised traffic, higher speeds, and unsealed shoulders can increase the probability of pedestrian crashes when walking along roads (McMahon et al., 2001). Tulu et al (2013), also states that lack of sidewalks can increase the risk of crashes twofold compared to roads that have footpaths. According to Tulu et al (2013), the International Road Assessment Programme (iRAP) pointed out that 84% of roads with pedestrians in developing countries lack sidewalks (WHO, 2013, p. 33). Therefore, pedestrians often tend to walk along roads, due to the absence of footpaths or shoulders. Tulu et al (2013) asserts that, due to financial constraints, most developing countries’ road networks in built-up areas are constructed without the provision of sidewalks.

Damsere-Derry, et al. (2010) asserts that even when sidewalks are present in African cities, they may be occupied by roadside vendors and hawkers, or pedestrian facilities may be constructed without adequately accommodating the volume of pedestrians, or the surface is uneven or of poor quality, in ways that discourage walking. These factors may lead to pedestrians walking along the road. In poor residential neighbourhoods, areas with high unemployment, and near markets, pedestrian volumes may be extremely high, driving pedestrians to walk along the roadways.

These differences in pedestrian friendly infrastructure also seem to be related to different cultural conceptions of walking as a mode of transport. There seems to be a higher valuation of motorized transport over walking in African countries, compared with European countries. This means that driving a car is viewed as far more prestigious than walking. In an interview study with stakeholder in transport policy and practice in African countries, Benton et al (2023) report that interviewees perceived that walking is undervalued in policy and practice in African countries. They said that there is a continued focus on motorized transport among transport and land-use planning decision makers, as large road investment projects are a sign of progress, and the beliefs that it may foster economic growth (UN Environment, 2016). Interviewees perceived that there is insufficient funding allocated to walking infrastructure and services in comparison to other modes of transport. As a result, walking is less safe, more challenging, and unpleasant than in European countries.

When it comes to traffic safety culture, several studies of vehicle pedestrian collisions find that the risk of pedestrian accidents increase with increasing car driver violations, as well as pedestrian violations. For example, Chakravarthy et al (2007) note that in 18% of fatal pedestrian collisions, the car drivers had consumed alcohol. Additionally, drivers’ non-compliance with speed limits is another risk factor. Operationalizing national traffic safety culture partly as descriptive norms, Nævestad et al (2025) measure traffic safety culture as the level of road safety violations (e.g. aggressive violations, drink driving, lacking seat belt use) that road users expect from other drivers in their country. Descriptive norms may influence behaviour by providing information about what is expected, accepted and normal behaviour in traffic in our country, thereby creating a “mild social pressure” to do as the others do (Cialdini et al., 1990; Nævestad et al., 2019).

To examine the influence of infrastructural and cultural factors on pedestrian safety, the study examines pedestrian safety and influencing factors in three African countries (Tanzania, Ghana, Zambia) with three EU countries with record of excellence in traffic safety and practicing Safe Systems principles (Norway, Netherlands, Sweden). The selection of the three African and three European countries was based on their contrasting levels of Safe System implementation. Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands are global leaders in road safety and were the first to adopt the Safe System approach. Beginning around the year 2000, with initiatives such as Vision Zero and Sustainable Safety, these countries developed road safety management systems designed to minimize fatalities and serious injuries by accounting for human error and physical vulnerability. In contrast, Ghana, Tanzania, and Zambia were included because they have not yet implemented the Safe System, record substantially poorer safety outcomes, and represent diverse parts of sub-Saharan Africa. Including countries from different regions of the continent helps reduce the risk of regional bias and supports broader relevance of the findings within the African context.

Comparing numbers of road fatalities per million capita in 2021, as estimated by the WHO (2024) the numbers in Norway, Sweden and the Netherlands were 15, 21 and 34 killed per million inhabitants, while the numbers in Ghana, Zambia and Tanzania were 259, 171 and 158 killed per million inhabitants.[1] Thus, the fatal road accident rate per capita was on average 8.4 times higher in the three African countries than in the three European countries. The different levels of Safe System implementation in the studied European and African countries are likely to influence the accident involvement of the pedestrians in the African countries.

Previous research has also identified factors at the individual level, which influence pedestrian safety. The first is Pedestrian behaviour. McIlroy et al (2020) examined the relationship between pedestrian behaviours and pedestrian accident involvement and found that pedestrians that had never been involved in an accident scored significantly lower on aggressive pedestrian violations than those that had been involved in one, or more than one accident. Examples of aggressive pedestrian violations are e.g. “I get angry with another road user (pedestrian, driver, cyclist, etc.), and I yell at them”, “I get angry with another road user (pedestrian, driver, cyclist, etc.), and I make a hand gesture”. Other relevant safety influencing factors are Demographic factors. Sex. Males are overrepresented in pedestrian fatalities. Zhu et al (2013) find that the pedestrian death rate per person-year for males was 2.3 times that of females. Age. Chakravarthy et al (2007) state that children and older adults are most vulnerable to being struck by a motor vehicle. Moreover, compared to younger patients, older adults experience longer hospitalization, more complications and higher mortality rates (Chakravarthy et al., 2007).

1.2. Aims

The aims of the study are to examine the following among the pedestrians in three European and three African countries:

-

Pedestrians’ perceptions of the level of pedestrian friendly infrastructure, pedestrian friendly traffic situation, and pedestrian friendly traffic safety culture,

-

Pedestrians’ accident involvement, and

-

Factors influencing pedestrians’ accident involvement.

1.3. Hypotheses

Comparing the situation of pedestrians in European versus African countries, we have the following hypotheses:

-

Pedestrians in African countries perceive the traffic system (i.e. the pedestrian infrastructure, traffic situation) and traffic safety culture to be less pedestrian friendly, compared with pedestrians in the European countries.

-

Pedestrians in African countries experience a higher level of accident involvement compared with pedestrians in the European countries.

-

The accident involvement of both European and African pedestrians is related to factors at both the individual level (behaviour, demographic factors) and system level (infrastructure, traffic safety culture).

2. Methods

Several methods and approaches were used. First, European researchers have conducted field works in the African countries. Second, individual interviews and focus group interviews have been conducted with road users and stakeholders in the African countries. Third, this served as a backdrop for developing a large-scale quantitative survey.

2.1. Fieldwork

The study leader (main author) visited Zambia in 2022, and Tanzania in 2023 and 2024, and Ghana in 2023 and 2025. He stayed for 6–7 days each time. Provisional field work notes were made (as well as photographs and videos), focusing on e.g. the: 1) composition of road users, 2) interaction between road users (e.g. the level of cooperation or conflict), 3) the quality of road and road infrastructure, 4) facilitation of the road system for vulnerable road users and 5) car drivers respect for and consideration of vulnerable road users and motorcyclists, 6) general risk taking behaviours (e.g. speeding, seat belt use, helmet use) and 7) the situation of children in traffic. The focus of the field notes was on comparing the situation in the African countries with the situation in the European countries (i.e. Norway, Sweden, Netherlands). A second Norwegian researcher has also been to Ghana and Tanzania to observe and discuss results from the fieldwork. The purpose of the fieldwork was that the Norwegian authors should experience traffic in the African countries, to get a deeper understanding of the background of the data in the survey.

2.2. Focus group interviews

Focus group interviews with 48 stakeholders were conducted in three African countries: Ghana, Tanzania and Zambia. The main purpose of the individual interviews and focus groups was to get information about and discuss the relevance of items measuring road safety violations and items measuring traffic safety culture, including to get insights into the most relevant road safety challenges and behaviours, beliefs and norms that might be important in these contexts. Other issues that were discussed were factors influencing traffic safety culture, e.g. road user interaction, enforcement, the composition of road users (e.g. vulnerable road users, motorcyclist), economy, urban planning. A semi-structured interview guide was applied, which includes questions about the most important types of road accidents, typical scenarios involved in these accidents (e.g. who, where and when), typical risky road user behaviours in different settings, relevant road safety measures to address the most prevalent accident types and road safety challenges. In addition to asking about this, we also showed lists of relevant items that we planned to use to measure traffic safety culture, to compare this across European and African countries. We asked about the relevance of the items, and whether interviewees had suggestions to more items to be added, based on their views on risky road user behaviours that are prevalent in their (African) country.

Interviews were conducted digitally via Microsoft Teams between October 2023 and January 2024, with interview durations ranging from 40 minutes (1 individual interview) to 2,5 hours (for group interviews). We employed a strategic sampling method, where the interviewees were selected based on criteria relevant to the research questions. We focused on assembling a sample that represented various roles in traffic safety work, including e.g. people working in authorities (e.g. national road authorities, and other authorities working with road safety), NGOs working with road safety (e.g. vulnerable road users, motorcycle safety, children safety) and people working as road safety researchers (cf. Appendix, A1). We conducted thematic analyses of the focus group interviews, systematically recurring themes in the interviewees’ descriptions of specific topics (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

2.3. Quantitative survey

2.3.1. Recruitment of respondents

The survey data was mainly collected during the first half of 2024. The aim of the survey was to include a representative sample of pedestrians in the capitals/largest cities of the participating countries. Capitals were chosen in all the participating countries, except Tanzania, where we choose the largest city (Dar es Salaam), which was the capital until 1996. The survey data in the three African countries was collected through personal interviews in Lusaka, Accra and Dar es Salaam. Accessing respondents through web surveys was not feasible in these countries, as only a few people have e-mails and internet access, presumably people in favourable economic positions and/or with high levels of education. To obtain representative samples of pedestrians, teams of interviewers therefore went out in traffic to recruit respondents to participate in personal survey interviews. In some cases, respondents who were in a hurry were given the link to the survey, so they could answer the survey at home. To maintain representativity, interviewers ensured to recruit respondents in different areas of the cities and at different times. We assumed that this would avoid recruiting only particular segments of road users. The Norwegian respondents were recruited from a representative sample of respondents from the capital Oslo, who have agreed to participate in surveys from the Institute of Transport Economics. The Swedish and Dutch respondents were recruited from representative samples of respondents from the capitals Stockholm and Amsterdam, using representative panels of respondents from the company Norstat. Surveys were collected using the official languages in all countries, e.g. English in Ghana and Zambia, Swahili in Tanzania, Dutch, Swedish and Norwegian. Professional translators were used, and translations were tested and validated by native speakers, who are traffic researchers. In an attempt to increase response rates, Norwegian respondents were informed that they could, if they wanted, participate in a draw for a present card of 3000 NOK (260 Euro). The Norstat respondents in Sweden and Netherlands are part of a panel which means that they get points for participating in surveys.

Respondents in the survey were filtered in two steps. First, the study only includes results for respondents who are of the same nationality as their country. The reason is that we focus on questions related to national traffic safety culture. Previous studies have indicated that respondents who are immigrants in their country might rate different factors higher than domestic respondents, e.g. due to deference to authority and their immigrant status (Guldenmund et al., 2013). Results for the immigrant respondents will be presented in other publications, also including these. Second, we have filtered out 353 respondents who answered the survey in a shorter time than 2,5 minutes. The speed of respondents’ survey response time is an established measure of survey response quality (Huang et al., 2012; Zhang & Conrad, 2014). There are no established threshold limits for excluding too fast respondents, but one criterion is that speeding involves answering the survey faster than it is possible to read the questions (e.g. 300 milliseconds per word) (Zhang & Conrad, 2014). We assess that reading all the 50 questions in the survey fast takes about three minutes. Thus, our threshold value is somewhat below that. The reason is that survey speeding does not necessarily apply to all sections in surveys.

2.3.2. Survey themes

The survey includes the following themes: Demographic variables, How often, where and why the pedestrians walk, main means of transportation, Pedestrian road safety violations, Perception of pedestrian friendly infrastructure, Pedestrian traffic situation, Traffic safety culture measured as descriptive norms, Sociocultural position of pedestrians, Pedestrians’ accident involvement (See the appendix for a detailed description).

2.3.3. Quantitative analyses

Several sum score indexes, based on the questions in the surveys were constructed. When making these sum score indexes, we considered the following: First, we assessed the importance and relationship between questions based on previous research, indicating that the questions measure the same underlying phenomenon. Second, we conducted exploratory factor analyses based on the data from all the countries taken together, examining whether questions load on the same factor, or different factors. Third, we conducted analyses of internal consistency, including Cronbach Alpha estimate with: “scale if item deleted” analyses, to identify questions that seem less important, and if removed would increase the internal consistence of the sum score index. The description of the survey themes and indexes, the full wording of the survey questions are included in the Appendix (A2). Means and standard deviations are included in Table 2.

We have conducted a multivariate regression analysis, to examine the factors influencing whether respondents have been involved in a traffic accident with a vehicle, while walking in the last two years. Independent variables are included in successive steps, with the most basic ones added first, followed by the other independent variables. We use binary logistic regression analysis, as the dependent variable is dichotomous (accident: yes/no).

The multivariate regression analysis is used to test Hypothesis 3, which has assumptions about relationships between key variables. Hypothesis 1 concern differences between African and European pedestrians, that are measured with different statements. Answer alternatives for these statements generally range from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). We generally combine statements measuring the same underlying phenomenon into sum-score indexes, based on e.g. assessments of Cronbach’s Alpa. To test Hypothesis 1, we compare the mean scores of African and European pedestrians on the sum-score indexes, using one-way ANOVA tests, which compare whether the mean scores are equal (the null hypothesis) or (significantly) different. In addition, chi-square analyses were conducted to test the hypotheses concerning the relationships between categorical variables, e.g. accidents for Hypothesis 2.

3. Results

3.1. Sample description

A total of 1862 respondents participated in the survey, of whom 40 percent (n=753) were recruited from one of the African countries. Basic sample characteristic by geographical area of recruitment is shown in Table 1. Overall, 47 % of respondents were female, although this share was slightly higher in European countries than in the African countries.

| Characteristic | European | African | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 52% | 39% | 47% |

| Male | 48% | 61% | 53% | |

| Age | <26 yrs | 8% | 31% | 17% |

| 26-35 yrs | 21% | 38% | 14% | |

| 36-45 yrs | 18% | 19% | 18% | |

| 46-55 yrs | 22% | 9% | 16% | |

| >55 yrs | 32% | 3% | 10% | |

| Education | Primary school | 2% | 12% | 6% |

| High school | 23% | 36% | 28% | |

| University 3-4 yrs | 36% | 19% | 30% | |

| University 5 yrs | 39% | 32% | 36% | |

| Total | n | 1109 | 753 | 1862 |

The European respondents are generally older than the African respondents, with ten times more respondents in the age group over 55 years old in the European sample, and nearly three times more respondents under 26 years old in the African sample. Regarding levels of education, there are higher shares of respondents in the lowest education level among the African participants. More detailed breakdowns of participants’ gender distribution, age groups and education per country is presented in the Appendix (A3).

A majority in both samples (about 65%) walk daily as a means of transport (see Appendix; A4), though African respondents walk for longer periods on average. We asked respondents how long they usually walk on a typical day where they walk to reach destinations. The African respondents walk twice as many minutes on average on a typical day where they walk (96 minutes versus 45 minutes). In response to the statement “Walking is one of my main means of transportation,” 61% of European pedestrians agreed (30% somewhat and 31% totally), while 58% of African pedestrians agreed (13% somewhat and 45% totally). When asked if they walk because they have no other choice, only 19% of European respondents agreed (15% somewhat and 4% totally), compared to 33% of African respondents (15% somewhat and 18% totally). For the statement “I walk for the pleasure of it,” agreement was substantially higher among Europeans, with 83% agreeing (34% somewhat and 49% totally), while only 34% of African respondents agreed (14% somewhat and 20% totally). Mean scores, standard deviations and p-values for these statements, comparing European and African respondents, are provided in Table 2.

3.2. Results based on fieldwork

The study presents findings from fieldwork conducted in selected African urban areas, with a particular focus on traffic conditions as perceived from a Northern European perspective. The observations reveal a markedly different traffic environment compared to European contexts, especially those in countries like Norway, Sweden and the Netherlands.

Traffic in the studied locations is characterized by high levels of congestion during peak hours. Informal economic activities are also integrated into the traffic landscape; numerous street vendors (hawkers) were observed selling goods directly in the roadway, including on stretches with relatively high speed limits. However, traffic congestion often slowed vehicles to a halt, effectively transforming these areas into temporary marketplaces.

Pedestrian activity is significant, with many individuals walking along or crossing busy roads. However, there were no observations of wheelchair users and very few bicyclists, suggesting limited accessibility and safety for these groups. The road infrastructure generally lacks dedicated space or protections for vulnerable road users. Physical separation between pedestrian and vehicular traffic is rare, even on high-speed roads, some of which traverse residential and village areas where children are present. Moreover, street lighting is limited, pedestrian crossings are seldom regulated by traffic lights, and open roadside ditches pose additional hazards, particularly in low-visibility conditions.

A recurrent interaction pattern involves what may be termed a “right of the strong,” where larger vehicles exert dominance, especially in congested conditions. This dynamic places more vulnerable road users—such as pedestrians, motorcyclists, and cyclists—at a disadvantage, requiring them to yield and adapt to more aggressive driving behaviours. Larger vehicles and assertive drivers frequently “win” right of way.

In Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, the traffic situation on main roads was particularly striking. The dominant driving behaviour observed resembled a “race to get ahead,” with road users consistently attempting to advance as quickly as possible. This behaviour led to frequent overtaking, sudden lane changes, and other manoeuvres that created a chaotic traffic environment. Given the mix of two-way traffic and vehicles entering from side roads, researchers documented a high incidence of near-misses and traffic conflicts during nearly every observational trip. There was a prominent presence of motorcyclists in Tanzania. Motorcyclists frequently navigate between cars, often using narrow gaps in traffic flow.

Pedestrians were often seen navigating this hazardous environment by walking along busy roads, crossing between fast-moving vehicles, or running to avoid oncoming traffic. The lack of respect for pedestrian right-of-way stood in contrast to Northern European norms, where motorists commonly yield to pedestrians. Furthermore, the road infrastructure in the studied African cities appeared to be less adapted to the needs of non-motorized and vulnerable road users. This includes limited signage, few safe crossings, and little infrastructure designed to accommodate those on foot or using mobility aids. In summary, the fieldwork highlights substantial differences in traffic safety culture, behaviour, and infrastructure between the studied African settings and Northern European contexts.

3.3. Perceptions of infrastructure and traffic safety culture

The focus of this section is the first aim of the study, which is to examine pedestrians’ perceptions of the level of pedestrian friendly infrastructure and pedestrian friendly traffic safety culture. Table 2 provides mean scores for key items.

| Continents | European | African | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indexes and items | M | S.D. | M | S.D. | p |

| Pedestrians’ reasons for walking | |||||

| Walking is one of my main means of transportation | 3.5 | 1.4 | 3.4 | 1.7 | .025 |

| I walk because I have no other choice | 2.2 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 1.6 | < .001 |

| I walk for the pleasure of it | 4.2 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 1.6 | < .001 |

| Public transport is one of my main means of transportation | 3.5 | 1.5 | 3.8 | 1.5 | < .001 |

| Private car is one of my main means of transportation | 2.4 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 1.7 | n.s. |

| Pedestrian friendly infrastructure index (4 items): | 16.4 | 3.2 | 10.9 | 4.8 | < .001 |

| The roads where I usually walk...have sidewalks dedicated for pedestrians | 4.3 | 1.0 | 2.8 | 1.6 | < .001 |

| ...have walkways that are well separated from vehicles and motorcycles | 3.8 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 1.5 | < .001 |

| ...have crosswalks where I can safely cross the road | 4.2 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 1.5 | < .001 |

| …have streetlights that sufficiently light up the road/street when it is dark | 4.1 | 1.0 | 2.8 | 1.6 | < .001 |

| ....are very challenging to use as a pedestrian because of obstacles in the roadside | 2.2 | 1.2 | 2.7 | 1.5 | < .001 |

| Traffic situation index | 6.3 | 2.1 | 8.0 | 2.2 | < .001 |

| The speed of vehicles/motorbikes is too high | 3.2 | 1.1 | 3.9 | 1.3 | < .001 |

| The speed and amount of traffic create a sense of danger for pedestrians | 3.1 | 1.2 | 4.1 | 1.2 | < .001 |

| Traffic safety culture index (5 items) “When walking on roads in my country, I expect the following behaviour from car drivers: | 7.8 | 3.3 | 9.9 | 4.6 | < .001 |

| That they become angered by a certain type of driver and indicate their hostility by whatever means they can | 1.7 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 1.3 | < .001 |

| That they sound their horn to indicate their annoyance to another road user | 1.7 | 0.9 | 2.7 | 1.4 | < .001 |

| That they overtake a slow driver on the inappropriate side | 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 1.2 | n.s. |

| That they drive when they suspect they might be over the legal blood alcohol limit | 1.4 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 0.9 | .090 |

| That they drive without using a seatbelt | 1.3 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 1.4 | < .001 |

| Traffic safety culture (1 item) Social valuation of walking and pedestrians | |||||

| People who drive a car to their job are respected more than people who walk to their job | 2.0 | 1.1 | 3.9 | 1.4 | < .001 |

| The road system in my country is made for cars and not for pedestrians | 3.0 | 1.2 | 3.1 | 1.6 | .093 |

| Pedestrian violations index (4 items) | 5.1 | 1.9 | 6.2 | 3.5 | < .001 |

| I get angry with another road user (pedestrian, driver etc.), and I yell at them | 1.5 | 0.8 | 1.7 | 1.2 | < .001 |

| I get angry with another road user (pedestrian, driver etc.), and I make a hand gesture | 1.4 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 1.3 | < .001 |

| I get angry with a driver and hit their vehicle | 1.1 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 1.2 | < .001 |

| I cross very slowly to annoy a driver | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 1.1 | < .001 |

3.3.1. Pedestrian friendly infrastructure

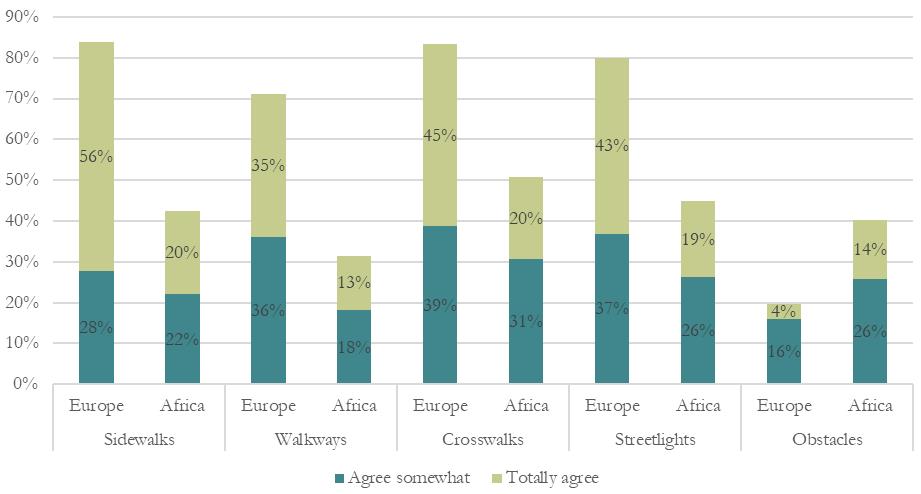

As illustrated in Table 2, the degree of pedestrian friendly infrastructure reported is higher among the European respondents. These results are also visualised in Figure 1, which shows the shares agreeing with the statements. The percentage points agreeing with statements in the European pedestrian sample is generally around forty or thirty percentage points higher than in African pedestrian sample. The statements says e.g. that the street/roads were the pedestrians usually walk: “…have sidewalks dedicated for pedestrians, …have walkways that are well separated from vehicles and motorcycles, …have crosswalks where I can safely cross the road” (All the statements are provided in Table 2).

Figure 1 shows that the European respondents generally agree more with the positive statements about pedestrian friendly infrastructure. This indicates more pedestrian friendly infrastructure for the European pedestrian respondents. In line with Hypothesis 1, Anova tests show that the sum score index of four of the five questions (excluding obstacles) was significantly higher among European respondents (16.4 points) than among the African respondents (10.9 points) (p < .001) (min:4, Max:20) (cf. Table 2).

During the focus groups, the lack of infrastructure for vulnerable road users was emphasized and discussed in all three African countries. There is a lack of sidewalks, pedestrian crossings and bike lanes. There are often no protective barriers or railings to protect pedestrians and cyclists from motorized transport. Participants in Zambia stated the need to recognize and build infrastructure for vulnerable road users:

Some accidents may happen because there’s improper lighting, especially during the night. Some drainages are very unfavourable in urban areas. They are made of concrete and they’re quite deep. […] I mean, there’s so much more one can look into to improve the designs and safety of people, especially, I think, the vulnerable road users need recognition as part of traffic.

Encroachment along the roadside, including obstacles (cars, shops etc.) were mentioned as a problem for pedestrians, giving less space for footpaths.

3.3.2. Traffic situation: perceived traffic volume and vehicle speed

Two statements measure pedestrians’ perception of traffic volume and speed on the roads where the pedestrians in the study usually walk (Traffic situation): “The speed of vehicles/motorbikes is too high” and “The speed and amount of traffic create a sense of danger for pedestrians.” (cf. Table 2). We made a sum score index of the two questions, and the score of European respondents was 6.3 points, while the score of African respondents was 8.0 points (min:2, Max:10). Anova tests shows that the differences between European and African respondents was statistically significant (p<.001) on both questions. This is in accordance with Hypothesis 1. Looking at shares agreeing with the statements, we see that, 43% of the European pedestrians agree, while 75% of the African pedestrians agree with the first statement. When it comes to the second statement, 45% of the European pedestrians agree, while 82% of the African pedestrians agree. This indicates a more pedestrian friendly traffic environment in Europe.

3.3.3. Traffic safety culture

First, we measure traffic safety culture as descriptive norms. The index score measuring traffic safety culture as descriptive norms (min: 5, Max: 25) was higher among pedestrians in African countries (mean score =10.8) than in European countries (mean score = 7.9), indicating that African respondents expect more violations among drivers, especially related to aggressive driving (cf. Table 2). Anova tests indicate that the difference was statistically significant (p<.001). This is in accordance with Hypothesis 1.

This result was also indicated in the focus group interviews. Participants emphasized that drivers and riders generally tend to be in a hurry. They want to get ahead as fast as possible, and this leads to dangerous overtaking on the roads:

Usually drivers may be ignorant, sometimes they want to rush ahead to overtake.

We also observed this in the fieldwork. When describing motorcyclists in traffic, it was mentioned that:

There is a surge in motorcyclists because of the whole delivery business. So, you will find that most of them [motorcyclist], on the road are impatient so they will not follow their proper road rules. They will be swerving around in traffic.

Second, we measure traffic safety culture as the societal valuation of pedestrians. As for the perceived societal valuation of pedestrians, we see a clear difference among pedestrians on the two continents (cf. Table 2). The statements measuring this are: “People who drive a car to their job are respected more than people who walk to their job”. “The road system in my country is made for cars and not for pedestrians.” Anova tests shows that the difference between European and African respondents was statistically significant (p<.001) on the first statement, but only at the 10% level for the second question (p=0.093). The latter is probably related to the ambiguous nature of the statement. This statement may be interpreted both as a descriptive statement (how it is now), and as a normative statement (how it should be). When we look at shares agreeing with the statements, the shares agreeing with the first statement was more than seven times higher in the African than in the European sample (70% vs. 8%). When it comes to the second statement, 39% of European pedestrians agreed, compared to 51% of the African pedestrians.

Focus group participants indicated that cars are seen as a sign of progress, while pedestrians are valued lower than cars. Thus, when people get sufficiently wealthy, they want to own a car. It was mentioned that:

A lot of people with access to money have decided to invest in their own vehicles…

People who drive a car are respected more than people who walk on the streets, and this also influences the interaction between road users. For example, it was mentioned that pedestrians have a lower status, and that motorized road users therefore are reluctant to stop:

Traffic officers, especially [the] police, know this. Few will stop for pedestrians.

One of the participants had moved from an African to a European country, at the time of the interview, and said that, seen from Europe, it was easy to see differences in traffic safety culture, especially when it comes to motorists’ respect for vulnerable road users:

Being on this other side of the world [i.e. in Europe] (…), you can see that the attitude of people is really different on the road: There’s respect you know.

This quote came in a discussion of whether car drivers stop for pedestrians who wants to cross the road.

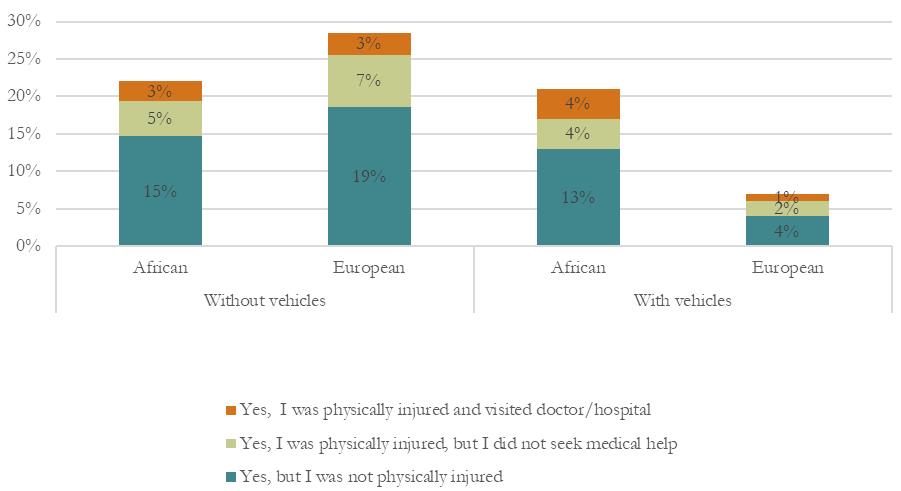

3.4. Accident involvement

The focus of this section is the second aim of the study, which is to examine pedestrians’ accident involvement. The share of respondents who had been in an accident involving a vehicle was three times higher among pedestrians in African countries (21 percent, among which 38 percent were injured) than among those from Europe (7 percent, of whom 43 percent injured). In contrast, involvement in accidents not including vehicles (incl. tripping, falling) was more common among pedestrians in European countries (29 %) than in the African countries (23 %). For both samples, 34-35 percent of those involved in a single accident reported that the accident caused them physical injury (cf. Appendix; A5). Based on Hypothesis 2, we assumed that pedestrians in African countries have been involved in more accidents compared to pedestrians in European countries. To test this hypothesis, Chi-square tests were conducted. The results showed that the associations between region and accident involvement were statistically significant in both cases (p=< 0.001). Specifically, the result for accidents involving vehicles supported Hypothesis 2, whereas the result for single pedestrian accidents (i.e., accidents without vehicle involvement) did not.

3.5. Factors influencing accident involvement

The focus of this section is the third aim of the study, which is to examine factors influencing accident involvement.

Results from logistic regression models for pedestrian accident involvement are displayed in Table 3.

| Variable | Mod. 1 | Mod. 2 | Mod. 3 | Mod. 4 | Mod. 5 | Mod. 6 | Mod. 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walking frequency | .892* | .902* | .905* | .920 | .897** | .899** | .883** |

| Age (>56=1, <56=0) | .410*** | .398*** | .425*** | .491*** | .502*** | .675 | |

| Education (University=1, Else=0) | .635*** | .650*** | .696** | .711** | .726* | ||

| Traffic safety culture | 1.060*** | 1.053*** | 1.043** | 1.030* | |||

| Pedestrian friendly infrastructure | .942*** | .946*** | .986 | ||||

| Pedestrian road safety violations | 1.059** | 1.053** | |||||

| European vs, African (Eur.=0 vs. Afr. 1) | 2.337*** | ||||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | .006 | .024 | .032 | .044 | .059 | .083 | .086 |

The results shows that walking frequency (where a high value implies less walking) is significantly related to pedestrians’ accident involvement; less walking is related to decreased probability of being involved in a pedestrian accident.

Results for the traffic safety culture index indicate that expecting a higher level of aggressive pedestrian violations from car drivers is related to increased probability of pedestrian accident involvement.

Additionally, while a higher level of pedestrian friendly infrastructure is related to decreased probability of pedestrian accident involvement, this is no longer true when controlling for European vs. African countries; the association between pedestrian infrastructure and accidents is in part explained by differences in the level of such infrastructure in African vs. European countries: the latter scores higher on the index.

The variable Pedestrian road safety violations is related to increased probability of pedestrian accident involvement, which means that the higher level of aggressive violations pedestrians report, the higher is their probability of being involved in an accident with a vehicle. This applies also when controlling for region.

The probability of having experienced an accident is higher among the pedestrians recruited from African countries, compared with the European sample, but overall, these variables explain only 9% of variation in pedestrians’ accident involvement.

4. Discussion

4.1. The importance of infrastructure

The first aim of the study was to compare pedestrians in the African and European countries’ perceptions of their walking infrastructure, traffic situation and traffic safety culture. We hypothesized that pedestrians in African countries perceive their road infrastructure, traffic situation and traffic safety culture to be less pedestrian friendly, compared with pedestrians in the European countries (Hypothesis 1). Our results support Hypothesis 1 when it comes to perceptions of infrastructure and traffic situation. This is also in accordance with previous research (Tulu et al., 2013; WHO, 2013), which has pointed to e.g. lacking sidewalks and lacking physical separation between vulnerable road users and motorised traffic.

4.2. The importance of traffic safety culture

Our results also support Hypothesis 1 when it comes to traffic safety culture and valuation of pedestrians. A unique contribution of the present study is that we compare the existence of pedestrian friendly traffic safety culture. Several studies of vehicle pedestrian collisions find that the risk of pedestrian accidents increase with increasing car driver violations, as well as pedestrian violations (Chakravarthy et al., 2007). Relevant car driver violations increasing the risk of pedestrian vehicle collisions are driving under the influence and over speeding (Chakravarthy et al., 2007). We measure traffic safety culture as pedestrians’ expected car driver violations in their country. More specifically this refers to descriptive norms, i.e. the level of violations (e.g. aggressive violations, drink driving, lacking seat belt use) that road users expect from other drivers in their country.

The valuation of pedestrians in a society is also an important aspect of traffic safety culture. The shares agreeing with the statement: “People who drive a car to their job is respected more than people who walk to their job” is seven times higher among the African respondents compared with the European respondents. Thus, there also seems to be a higher valuation of motorized transport over walking in African countries, compared with European countries. This is in accordance with what Benton et al (2023) has found for land-use planning decision makers prioritizations. We are unaware of previous studies which directly examine road users’ valuation of pedestrians versus car drivers.

4.3. Accident involvement

The second aim of the study was to compare accident involvement among pedestrians in the African and European countries. It was hypothesized that pedestrians in African countries would be involved in more accidents than pedestrians in the European countries (Hypothesis 2). Our results also support Hypothesis 2, but only when it comes to pedestrian accidents involving vehicles. Comparing numbers of road fatalities per million capita in 2021, data from WHO (2024) indicate that the fatal road accident rate per capita is in average 8,4 times higher in the three African countries than in the three European countries. We do not see this large difference in our data. On the other hand, we do not examine fatal pedestrian accidents in our study, but self-reported pedestrian accidents with and without personal injury.

4.4. The importance of system-level factors

The third aim of the study was to examine factors influencing pedestrian accident involvement. We compare the importance of person-related and system-related factors. It was hypothesized that the accident involvement of both European and African pedestrians was related to factors at both the individual level (behaviour, demographic factors) and system level (infrastructure, traffic safety culture). (Hypothesis 3). Results from our multivariate regression analyses support this hypothesis. The multivariate analyses examined the importance of influencing variables at both the person level and the system level. The indexes measuring pedestrian friendly infrastructure and traffic safety culture influenced accident involvement, until the variable European vs. African was included, indicating that infrastructure and culture is closely related to region.

This is in line with our result that the European countries score higher on the pedestrian friendly infrastructure index. This indicates the importance of the system level factors when comparing the situation of pedestrians across European and African countries. This is also a result of our study design. We expected that the different levels of Safe system implementation in African and European countries would influence pedestrian safety. Based on this, we could perhaps expect the infrastructure and traffic safety culture to be more important predictors of pedestrian accident involvement among the African respondents, but this is impossible to test with the current study design, which is based on differences across continents. Thus, separate multivariate regression analyses for African and European pedestrians result in lower explained variation than the one with both groups, and fewer statistically significant predictor variables.

Qualitative data and previous research also stress the importance of more underlying system characteristics and societal factors. When it comes to the traffic situation in the African countries, previous research has underlined that the high traffic volume and the congestion on the roads in several African countries is related to an insufficient or lacking public transport system. The lack of a viable organized public transport system leads to a high level of car drivers (Boateng, 2021; Hoose, 2021a). Previous research also points to land use and low level of urban planning (Boateng, 2021; Hoose, 2021b). Focusing on Accra in Ghana, Hoose writes that rapid urbanization with almost no governmental regulation and land-use planning has led to a considerable distance between residential areas and workplaces, resulting in a high level of daily commuters (Hoose, 2021b). These issues were also highlighted in the focus group interviews. It was mentioned that the transport sector is growing, and that there is an increasing share of commuters from rural to urban areas, with populations in residential areas growing every day. This leads to more traffic on the roads and more accidents.

Finally, our research also indicates the importance of person-related factors predicting accidents. This especially applies to pedestrian safety behaviour (aggressive violations) and demographic factors like sex, age, education. This is in accordance with previous studies (Chakravarthy et al., 2007; McIlroy et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2013).

4.5. Policy implications

The importance of material versus cultural factors. Our study indicates the importance of both factors related to pedestrian infrastructure and traffic situation and traffic safety culture and valuation of pedestrians. We may refer to pedestrian infrastructure and traffic situation as material factors and traffic safety culture and valuation of pedestrians as cultural factors. While the material factors must be dealt with through comprehensive and expensive infrastructure changes, the cultural factors are an issue for information and education campaigns. The material factors concern “changing the streets”, while the cultural factors concern “changing peoples’ minds”, or ways of thinking". Changing minds may not be as expensive as changing streets, but it may nevertheless be challenging.

Creating a pedestrian friendly infrastructure. Improving the infrastructure, making it more pedestrian friendly, is likely to improve safety for pedestrians, but this is, however, resource demanding. Key measures could be e.g. Mandating national pedestrian design standards that require sidewalks, crosswalks, street lighting, and traffic calming in all new road projects. Allocating dedicated urban budgets to non-motorized transport improvements. Launching low-cost interventions like painted crosswalks, speed humps, and bollards in high-risk areas as transitional solutions. Enabling community reporting apps or hotlines for identifying hazardous walking environments.

Creating a pedestrian friendly traffic situation through improved urban planning and development of a well-functioning public transport system. The survey indicates that African pedestrians report of too many cars on their roads and too high speed. Based on previous research (Boateng, 2021; Hoose, 2021a), it seems that improvement in land use and urban planning, including the implementation of an organized public transport system, are relevant measures to create a pedestrian friendly traffic situation (in addition to infrastructure measures). More concrete measures could be to: Strengthen land-use regulations to support mixed-use of the road infrastructure by vulnerable road users and motorists, walkable neighbourhoods. Invest in formal, affordable public transport networks that reduce car dependency and traffic volume. Implement car-reduction zones in central areas, with parallel development of safe pedestrian corridors. Integrate pedestrian planning into city masterplans (e.g. no new development should proceed without pedestrian infrastructure assessments).

Creating a pedestrian friendly traffic safety culture. The survey indicates less pedestrian friendly traffic safety culture in the African countries, because of the higher level of car driver violations. This is an issue that could be addressed by more efficient enforcement in the African countries. Another relevant measure is to provide information and education to car drivers, to teach them about the situation and needs of pedestrians, aiming to make the car drivers drive more careful and slower around pedestrians, stop for them etc. It could also be relevant to pilot school-based programs that teach children pedestrian safety and empower them as change agents within families.

Improving the Sociocultural position of pedestrians in the society. The survey shows a clearly different social status for pedestrians in the European sample than in the African sample. We can speculate that this is related to the status of cars as a sign of wealth in the African countries, indicating high socioeconomic status. Thus, driving a car resembles what Torstein Veblen refers to as “conspicuous consumption”, i.e. a public display of income and social status. In the European countries, it can be argued that the situation is opposite, driving a car to work is not a practice which gives high social status. Additionally, walking is to a greater extent acknowledged as a separate mode of transport in the European countries, both by citizens and stakeholders, along with car driving. This has implications for the construction of pedestrian friendly infrastructure, how car drivers interact with pedestrians, the sociocultural status of walking etc. Relevant measures to improve the sociocultural position of pedestrians in the society would be to provide information and education to both stakeholders (politicians, city planners etc.) and citizens stressing that walking is a separate mode of transport, with benefits for health, environment and safety. More concretely, this could involve measures like e.g. To develop positive messaging around walking as a modern, healthy, and environmentally responsible choice, not just a necessity. Highlight role models and public figures who walk—especially in government and media. Celebrate car-free events and pedestrian days in city centres to elevate visibility and enjoyment of walking. Incorporate walking into national transport strategies, recognizing it as a formal mode of transport deserving investment and policy attention. However, as we have seen, such measures should be combined with infrastructure measures and measures to improve pedestrian safety in the African countries, as many of these pedestrians have a high risk perception and avoid walking in several areas, as they fear traffic accidents.

4.6. Methodological weaknesses and strengths

We rely on both qualitative and quantitative data. This study presents fieldwork results, which involve main conclusions about the traffic in the studied African countries, seen from a Northern European perspective. These observations are useful, as the study compares factors influencing the situation of pedestrians across European and African contexts. Thus, we can use these observations to assess whether the observed survey differences, e.g. related to pedestrian infrastructure and traffic situation, are as expected based on our experiences in the different countries. Moreover, we can also use these data to assess whether there are unmeasured factors that we should have focused on. Together with interview data, fieldwork data has also been used to develop survey questions.

Comprehensive survey safety data are rarely available. The study contributes with new knowledge. There are few studies linking cultural factors with road safety, and even fewer studies comparing traffic safety culture across African and European countries. Additionally, comprehensive survey safety data are rarely available from African countries (UNECA, 2015).

Representativeness of the samples and possible self-selection in Europe. All the national samples have been drawn from representative populations. The European samples have been drawn from representative panels, and the African samples have been recruited from different city areas at different times. African pedestrian respondents in the study were recruited when they were walking on the street. European pedestrian respondents in the study were recruited through a survey of representative people in the capitals of the participating countries. People who never walk as a mean of transport, were filtered out. Given that the survey was addressed to pedestrians, we could perhaps assume there to be some self-selection among the European respondents, i.e. that people who walk often were more motivated to answer a survey about walking.

While the study recruited participants across six countries, there are notable differences in the demographic composition of the African and European subsamples, particularly in terms of gender and age. The African sample is skewed toward younger and male respondents, whereas the European sample includes a larger proportion of older adults and a more balanced gender distribution. These differences reflect broader demographic patterns and possible disparities in recruiting strategies, especially among older women in the African context. These differences should be taken into account when interpreting cross-regional comparisons, as age and gender are likely to influence pedestrian behaviour, risk perception, and vulnerability. Given the different demographic profiles in the European and African samples, it might be argued that the paper to some extent compares, young people in African countries who walk “because they have no other alternatives” with older people in European countries who walk “for the pleasure of it”. However, the observed age differences between the African and European samples reflect underlying demographic trends. According to UN estimates (2024), the median age in the three African countries included in the study ranges from 17 to 21 years, while it is around 40 years in the European countries (United Nations, 2024). Thus, the younger age structure in the African sample aligns with broader population patterns and should not necessarily be interpreted as a sampling bias. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that the limited representation of older adults in the African sample may affect comparability of age-related findings across regions.

Self-reported data. The study is based on self-reported data, which could be influenced by respondents’ memory, truthfulness, and social or psychological biases that may influence reporting. As noted by Nævestad et al. (2017), comparing cross-cultural samples is challenging, as different national samples may be influenced by different baselines, and as expectations may vary between national samples. The levels of experience with surveys and trust in anonymity may vary between national samples. It is difficult to conclude about the importance of this.

The selection of countries for the study. The European countries were selected for the study, as they are pioneers in Safe System implementation and have the lowest number of road fatalities per capita in the world. It is worth noting that the Netherlands’ status as a global leader in road safety has declined since 2010, when it ranked third in the world in terms of the lowest number of road fatalities per capita. We argued in the introduction, that the three African countries selected for the study span different sub-Saharan regions, helping to avoid regional bias and lending broader generalizability within the African context. It is, however, important to note that although the selected African countries offer some regional diversity within sub-Saharan Africa, they cannot represent the full spectrum of cultural, socioeconomic, and infrastructural variation across the continent. Still, their inclusion enables a cross-continental comparison that illustrates how differing transport policies, cultural valuations of walking, and institutional priorities may shape pedestrian risk. Importantly, this study also considers how broader structural issues—such as urban inequality and the social marginalization of non-motorized transport—contribute to disparities in pedestrian safety and infrastructure provision.

Positively worded questions are excluded. We originally included some positively worded questions among the survey questions measuring descriptive norms and road user behaviour. These are about what kind of behaviours respondents expect from drivers in their country e.g. “That they always stop for pedestrians who want to cross the road”, “That they always slow down, or drive more carefully, when there are pedestrians at the side of the road”. The challenge with these questions was that they are positively worded, and they followed negatively worded questions in the survey. Thus, several respondents commented that they had not realized the opposite wording before after they had finished the survey, and that they had “answered wrong”, or the opposite of what they intended on the positively worded questions. They recommended us to discard their answers on these questions. Looking at the results, we saw that they were contrary to what we expected, and contrary to comparative negatively worded questions in the survey.

Focus on continents. The study heavily uses the “European vs. African” dichotomy. While the focus on continents captures structural differences (e.g., infrastructure, culture), this grouping masks within-region heterogeneity, and limits nuanced analysis of country-specific factors. It could be mentioned that e.g., differences between Ghana, Tanzania and Zambia are glossed over in the current analytical framework. The same applies to differences between the European countries. Thus, this indicates an important area for future studies, also based on the present data.

4.7. Issues for future research

4.7.1. There is a need to measure traffic safety culture related to pedestrians

Based on qualitative fieldwork data, we have described types of road safety behaviour and traffic safety culture which seem to be important in the studied African countries. We describe this as a chaotic traffic environment, with a high number of conflicts and near misses. As this type of interaction created a great deal of conflicts and near misses, we also presuppose that this traffic safety culture also creates many traffic accidents. Vulnerable road users are particularly at risk in this traffic safety culture, as they do not have a separate infrastructure and often lack places to safely cross the road. Thus, this chaotic traffic environment and less regulated traffic safety culture could be part of the explanation for the higher fatality rate in the African countries. There is a need to measure this traffic safety culture in future studies, focusing on the interaction between car drivers and pedestrians. Future studies should also examine more types of pedestrian behaviours, e.g. pedestrians’ dangerous crossing behaviour, as well as more types of car driver behaviours, e.g. car drivers’ speeding or lacking respect for pedestrians who wants to cross the road (e.g. not stopping at zebra crossings). These are important areas for future research.

5. Conclusions

This is one of the few cross-continental studies to empirically link cultural perceptions (e.g. pedestrian status, driver norms) to pedestrian safety. Disparities in pedestrian safety between African and European countries are shaped by both infrastructure (material conditions) and traffic safety culture (norms, behaviour, status). While the former must be dealt with through comprehensive and expensive infrastructure changes, the latter is an issue for information and education campaigns. The former concerns “changing the streets”, while the latter concerns “changing peoples’ minds, or ways of thinking”. The latter may not be as expensive as the former, but it may nevertheless be challenging. We also discus more fundamental system-level factors like insufficient urban planning, less developed public transport system and poorer economy in African countries.

CRediT contribution statement

Tor-Olav Nævestad: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Sonja Forward: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology. Enoch F. Sam: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing—original draft. Jaqueline Masaki: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing—original draft. Daniel Mwamba: Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft. Thomas Miyoba: Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft. Filbert Francis: Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft. Anthony Fiangor: Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft. Jenny Blom: Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft. Ingeborg Storesund Hesjevoll: Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft. Aliaksei Laureshyn: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing—original draft.

Declaration of competing interests

The authors report no competing interests.

Funding

The present study is part of the EU-funded AfroSAFE project (Grant agreement ID: 101069500). The primary objective of the AfroSAFE project is to make a significant progress in propagation of the Safe System modus operandi within the road safety work context in African countries.

Declaration of generative AI use in writing

During the preparation of this work the authors used Chat GPT to check and improve language, and highlight parts of the text that involved repetition and/or too detailed information, and which could be removed, or moved to the appendix. This was used to improve the language and shorten the paper. Chat GPT was also used to translate relevant text from Norwegian to English. The output was reviewed and revised by the authors who take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Acknowledgements

We are very thankful to all the people who have contributed to the data collection in the participating countries, and all the respondents who have helped us by answering our survey. The present paper presents data from a larger study, which is presented in a EU-deliverable: Nævestad et al (2024): “Deliverable 5.3: Human factors and accident causation in selected African countries”

Ethics statement

The methods for data collection in the present project have been approved by Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (SIKT)which assists researchers with research ethics of data gathering, data analysis, and issues of methodology.

Editorial information

Handling editor: Mette Møller, Technical University of Denmark, Denmark.

Reviewers: Natalia Distefano, University of Catania, Italy; Wouter Van den Berghe, Tilkon Research & Consulting, Belgium.

Submitted: 1 February 2025; Accepted: 5 September 2025; Published: 8 December 2025.

Appendix

A1. Focus group participants

| Country | Dates | Numbera | Types of organisations, functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ghana | 23.10.2023 24.10.2023 |

16+9=25 | Authorities, researchers, NGOs |

| Zambia | 25.01.2024 06.02.2024 |

6+4+1=11 | Authorities, researchers, NGOs |

| Tanzania | May 2023 30.01.2024, 31.01.2024 |

2+5+5=12 | Authorities, researchers, NGOs working with road safety |

| Total | Authorities, researchers, NGOs |

A2. Description of survey themes

Demographic variables. All respondents were asked questions about age, gender, nationality and education.

How often, where and why the pedestrians walk. We asked pedestrians how often they walk to reach destinations, e.g. from home to work, from home to the shop, from home to the bus etc., using walking as a means of transport. Answer alternatives were: 1) Several times each day, 2) Every day, 3) 5–6 days a week, 4) 3–4 days a week, 5) 1–2 days a week, 6) A few days each month, 7) Less frequently than a few days each month, 8) I never walk to any destinations. Respondents who answered the latter were filtered out of the survey. We also asked: “What is the total duration of your walks on a typical day where you walk to reach destinations (e.g. work, shop, bus)? (minutes approximately for the whole day)”. We also asked the type of roads where they usually walk. Additionally, respondents were also asked to answer the following questions:

-

Walking is one of my main means of transportation

-

I walk because I have no other choice

-

I walk for the pleasure of it

-

Public transport is one of my main means of transportation

-

Private car is one of my main means of transportation.

Answers ranged from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree).

Pedestrian road safety violations. The survey included four questions about aggressive pedestrian behaviours: "For every ten trips you walk on streets/roads, approximately how often do you behave like this?:

-

I get angry with another road user (pedestrian, driver etc.), and I yell at them

-

I get angry with another road user (pedestrian, driver etc.), and I make a hand gesture

-

I get angry with a driver and hit their vehicle

-

I cross very slowly to annoy a driver.

The four questions were combined into a sum score index (Cronbach’s Alpha: .720). Pedestrian behaviour questionnaire (PBQ) items are based on McIlroy et al (2020). The four items above were chosen as they were found to be related to pedestrians’ accident involvement in a cross-cultural study, also involving countries from Europe and Africa (McIlroy et al., 2020).

The answer alternatives on the pedestrian road violations are absolute alternatives (e.g. Question: “For every ten trips, how often do you …?”, Alternative answers: 1) “Never”, 2) “Once or twice”, 3) “Three or four times”, 4) “Five or six times”, 5) “Seven or eight times”, 6) “More than eight times but not always”, 7) “Always”). Answer alternatives were changed from the relative answer alternatives e.g. in the PBQ, as previous research indicates that different demographic groups tend to interpret questions and formulations differently (i.e. what does “often” mean?) (Bjørnskau & Sagberg, 2005). Given that e.g. “often” and “very often” may have different meanings among respondents across countries and parts of the world, we use absolute answer alternatives on these questions.

Perception of pedestrian friendly infrastructure. The survey included five questions measuring the degree of pedestrian friendly infrastructure:

Please answer with regard to the streets/roads that you usually walk. These streets/roads:

-

…have sidewalks dedicated for pedestrians

-

…have walkways that are well separated from vehicles and motorcycles

-

…have crosswalks where I can safely cross the road

-

…have streetlights that sufficiently light up the road/street when it is dark

-

….are very challenging to use as a pedestrian because of obstacles in the road side.

The first four questions measure the level of safe system for pedestrians (pedestrian friendly infrastructure), and were combined into a sum score index (min:4, Max:20) (Cronbach’s Alpha: .838). The questions are based on, and builds further on Kim et al (2024).

Pedestrian traffic situation. The survey included two questions measuring the perception of traffic volume and speed on the roads where the pedestrians in the study usually walk. These two questions measure the “traffic situation”:

-

The speed of vehicles/motorbikes is too high

-

The speed and amount of traffic create a sense of danger for pedestrians.[2]

Questions were combined into a sum score index (min:2, Max:10) (Cronbach’s Alpha: .778). The questions are based on, and builds further on Kim et al (2024).

Traffic safety culture measured as descriptive norms. We measure traffic safety culture as descriptive norms (Cialdini et al., 1990), reflecting road users’ perceptions of what drivers in their country do. The survey included 5 questions on expectations to car drivers in road users’ country. The questions were introduced like this: “When walking on roads in my country, I expect the following behaviour from car drivers:”

-

That they become angered by a certain type of driver and indicate their hostility by whatever means they can

-

That they sound their horn to indicate their annoyance to another road user

-

That they overtake a slow driver on the inappropriate side

-

That they drive when they suspect they might be over the legal blood alcohol limit

-

That they drive without using a seatbelt.

Questions were combined into a sum score index (min:5, Max:25) (Cronbach’s Alpha: .798). Five answer alternatives ranged between 1 (none-very few) and 5 (almost all/all).

Sociocultural position of pedestrians. The survey included two questions measuring the sociocultural position of pedestrians:

-

People who drive a car to their job are respected more than people who walk to their job

-

The road system in my country is made for cars and not for pedestrians.

Pedestrians’ accident involvement. “During the last two years, have you been involved in an accident involving a vehicle (e.g. car, motorcycle) while walking on streets/roads?” Answer alternatives were: 1) No, 2) Yes, but I was not physically injured, 3) Yes, I was physically injured, but I did not seek medical help, 4) Yes, I was physically injured and visited doctor/hospital. Alternatives were combined into two categories: 1) No, 2) Yes.

A3. Demographic characteristics

| Country | Male | Female | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Norway | 49% | 51% | 544 |

| Sweden | 44% | 56% | 285 |

| Netherlands | 51% | 49% | 280 |

| Ghana | 62% | 38% | 258 |

| Tanzania | 70% | 30% | 250 |

| Zambia | 52% | 48% | 245 |

| Total | 53% | 47% | 1862 |

A4. Walking frequency

| Several times a day | Every day | 5-6 days a week | 3-4 days a week | 1-2 days a week | A few days a month | Less frequently | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African | 24% | 39% | 11% | 13% | 10% | 3% | 1% | 753 |

| European | 40% | 26% | 9% | 11% | 7% | 5% | 2% | 1109 |

| Total | 627 | 578 | 190 | 218 | 149 | 75 | 25 | 1862 |

A5. Accident involvement

The numbers are based on estimates from WHO (2024). The estimates from WHO are different from the official numbers of fatal accidents reported by national authorities, especially in the African countries. In Tanzania, the WHO estimated number of road fatalities is seven times higher than the official number reported by national authorities. ↩︎

This question relates to risk perception, but it is not used as a question about risk perception here, as it does not focus on the individual level, i.e. the risk perception of the respondent who is answering. Rather, the statement refers to the respondents’ assessment of the risk perception of the pedestrians using the streets in general. ↩︎